Preparing Early Career Librarians for Leadership and Management: A Feminist Critique

In Brief

This article explores the opportunities and challenges that early career librarians face when advancing their careers, desired qualities for leaders or managers of all career stages, and how early career librarians can develop those qualities. Our survey asked librarians at all career stages to share their sentiments, experiences, and perceptions of leadership and management. Through our feminist critique, we explore the relationships to power that support imbalances in the profession and discuss best practices such as mentoring, individualized support, and self-advocacy. These practices will be of use to early career librarians, as well as supervisors and mentors looking to support other librarians.

by Camille Thomas, Elia Trucks, and H.B. Kouns

Introduction

As early career academic librarians, we have had many conversations about what leadership and management look like in our lives and found that our experiences were not well-represented in LIS literature. Much of the research on leadership and management focuses on current experiences of those who already moved into leadership roles after decades of experience, not the process for moving into such positions.

We are a research team comprised of early career librarians who are cisgender women, including a woman of color and a queer white woman. Holly (H.B. Kouns) and Camille (Thomas) have experience with leadership, management and mentoring. Elia (Trucks) wants to lead from within her position and ensure equity in development opportunities. Our research questions were: What are opportunities and challenges for early career librarians interested in management as libraries evolve? Have we seen any progress on the calls to action regarding diversity, training, mentoring, and opportunities?

Literature Review

We started this study by looking for existing research specifically focused on how early career librarians navigated their experiences with leadership and management. We interpreted early career to include librarians with fewer than 10 years of experience, including pre-MLIS and paraprofessional experience. Leadership “is concerned with direction setting, with novelty and is essentially linked to change, movement and persuasion” (Grint, Jones, & Holt, 2017).

Training and Demographics

The initial source of formal training for most library managers comes from management classes in MLIS programs (Rooney, 2010). Outside of the MLIS, leadership and management institutes, trainings, and workshops are meant to help librarians develop leadership skills. The American Library Association (ALA) alone highlights over 20 different programs which offer self-assessment of participants’ skills and expose participants to leadership theories (Herold, 2014; “Library Leadership Training Resources,” 2008). Hines (2019) examined 17 library leadership institutes that reinforce the existing power structures of traditional leadership training and did not incorporate the values championed by ALA such as access, democracy, and social responsibility. Moreover, the requirements to attend retain exclusive barriers for marginalized professionals who may not be gainfully employed, able to take time off, or considered worthy of support, leaving middle managers of color and interim directors of color with even fewer opportunities to gain relevant experience before moving into senior leadership roles (Irwin & deVries, 2019; Bugg, 2016).

As the profession ages, librarians move up through the ranks of leadership and management by filling positions vacated by retirees. However, the delayed retirement of late career librarians especially affects women and people of color (POC) in the profession. Representation in academic librarianship has become more equitable for white women, from the male-dominated leadership landscape of the 1970s to greater advances between the 1980s and the 2000s (DeLong, 2013). Despite these advances in the number of women in leadership positions, there are still many areas where women have more experience yet make less pay (Morris, 2019). However, administrative job prospects look even bleaker for librarians of color than for white women since it is typical for librarians to learn leadership and management practices on the job only after moving into the role (Ly, 2015; Rooney, 2010). While there are efforts in the profession (particularly within the Association of Research Libraries (ARL)) to recruit diverse students and employees into librarianship, there is not as much emphasis on retention and advancement. Some librarians of color also see the amount and type of experience required for entry level positions as a barrier, as it reinforces homogeneity in libraries (Chou & Pho, 2017). This is evident in the demographics of university libraries which are 85% white and 15% minority. According to the annual salary statistics published by ARL (Morris, 2019), the overall makeup of people working in ARL libraries is 63% female and 36% male, and statistics for leadership in those libraries (directors, associate directors, heads of branches, etc.) is relatively proportionate. Out of those, 109 are directors of ARL libraries, of which 10 identify as people of color. (Morris, 2019).

Qualities & Skills

Historically, Masculine-coded, agency-based leadership qualities such as “assertion, self-confidence and ambition” have been associated with successful leaders in North America (Richmond, 2017). However, as more women and millennials or Gen Xers are in positions of power (Phillips, 2014), valued leadership qualities have begun to include communal, feminine-coded traits like “empathy, interpersonal relationships, openness, and cooperation” (Martin, 2018). They continue, “[Baby] Boomers, Gen Xers, and Millennials all [want] a leader who [is] competent, forward-looking, inspiring, caring, loyal, determined, and honest” (Martin, 2018). Feminist scholars address the implicit associations of certain skills such as shared power, recognizing privilege, building partnerships, and self-advocacy, combining attributes of communal and agency-based skills (Higgins, 2017; Askey & Askey, 2017; Fleming & McBride, 2017) with specific identity performance, rather than effectiveness or value (Richmond, 2017).

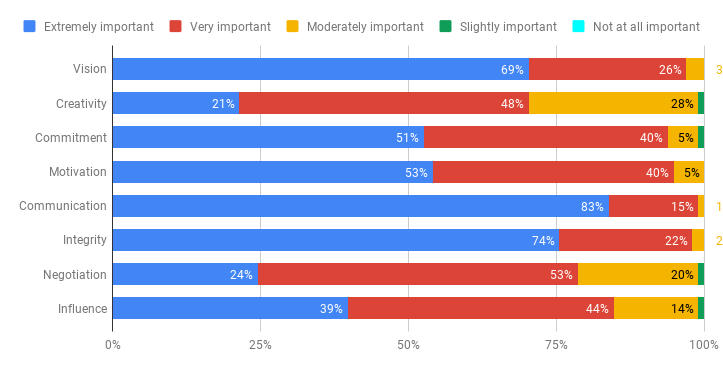

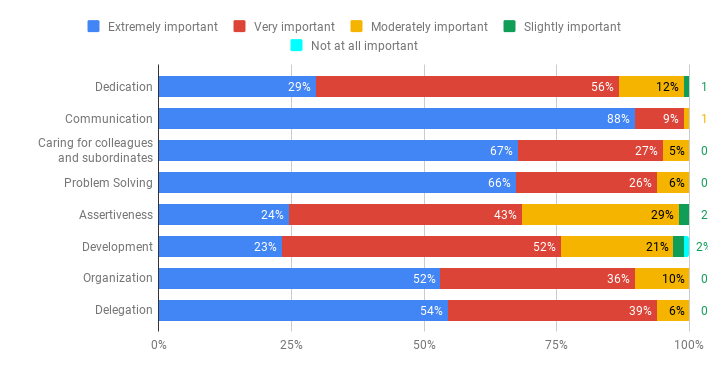

Hierarchical power structures have traditionally consolidated both leadership and management roles and thus, librarians needed to gain recognition through years of experience with both to advance. Leaders focus on high-level initiatives and managers focus on granular initiatives, therefore the skills that are needed to be effective in each role are different. The most valued leadership qualities include creativity, vision, and commitment, while the most valued management qualities include dedication, communication, and caring for colleagues and subordinates (Phillips, 2014; Young, Powell, & Hernon, 2003; Aslam, 2018; “Leadership and Management Competencies,” 2016; Martin, 2018; Stewart, 2017). As a result, many mid-career and late-career librarians “drift” into leadership positions because they are believed to have gained the necessary skills through years of experience with a variety of projects, personnel, and institutional developments (Ly, 2015; Bugg, 2016). Those who experience “leadership by drift” are appointed, usually without much self-reflection or choice (Ly, 2015). For example, library leaders are most often appointed as an interim leader, and 80% of those interim leaders are then hired without any outside recruitment (Irwin & deVries, 2019). This led us to believe that “drifting” was the primary path librarians could take into leadership positions.

In contrast, there are few accounts of librarians who actively sought leadership and management positions. Pearl Ly’s (2015) trajectory from interim to permanent dean included earning a PhD, participating in leadership training programs, and peer-mentoring from other administrators. Ly always intended to move into a leadership or management position, an intention of ambition which stands out from many other librarians, and serves as evidence of how ambition can accelerate the process of acquiring skills and training. Ambitious librarians forgo the long timeline of traditional “drift” (usually predicated on being appointed into positions after decades of demonstrating skills).

The topic of ambition has many nuances and challenges, especially in light of the hegemonic representation of who traditionally becomes a leader in librarianship. A respondent in Chou and Pho’s 2017 study shared an experience in which a Latina woman’s ambition to be a branch manager within five years was scoffed at by a hiring committee and she was not hired in the end. The respondent believed the candidate was seen as aggressive, but did not believe the committee would have had the same impression of a white male. Unlike Ly’s case, responses in Bugg’s 2016 survey of people of color in middle management positions show alternative paths to leadership. Respondents reported having the skills and desire for the work described in a position that had leadership and management responsibilities, but not necessarily the ambition to move up. Many respondents participated in preparatory activities (such as leadership training, doctoral degrees, career coaching, etc.) but only one expressed desire to move from middle management to senior leadership. They cited reasons for not wanting to advance such as the elimination of tenure, dissonance with personal values, and lack of motivation. This led us to wonder if there is a discrepancy between the skills needed and the skills valued.

Challenges

Once in positions with leadership and management responsibilities, librarians with ambition face different challenges. 32% of interim library leaders had fewer than five years of leadership and residency at their institutions when they were appointed to interim positions (Irwin & deVries, 2019). Several noted colleagues having difficulty accepting them as leaders, especially when length of service was not a criterion for appointment. Chou and Pho (2017) note common experiences in which female librarians of color were more likely to have their intelligence, qualifications, and authority questioned. Early career librarians in the study attributed perceived incompetence to looking young in addition to being a person of color and a woman. Women of color managers often experienced patrons who did not believe they were the person in charge. Similarly, Bugg (2016) found that many librarians of color felt apprehension about moving into senior leadership positions due to lack of exposure to senior leadership networks and incompatible organizational values. Before advancement, librarians were trained in both leadership and management externally. Afterwards, they discovered less access to and support for opportunities, such as lobbying for department needs, not feeling supported by senior leadership during difficult decisions, and lack of exposure to or not receiving opportunities.

Additionally, alternative types of leadership are not valued by traditional career advancement. Phillips (2014) highlights the “transformational leadership” type, which focuses on progressing organizational change, as the type of leadership commonly discussed in librarianship. In this style, collaboration among librarians is championed by the profession, as it is seen as necessary for progress. However, there is dissonance between valuing collaboration and recognizing demonstrations of leadership skills in collaborative work. This can be seen in the servant leadership style, currently popular in libraries (Richmond, 2017). Douglas and Gadsby’s 2017 study of instruction coordinators shows this imbalance. Instruction coordinators do a great deal of feminized “relational” work—supporting, helping, collaborating—and yet they are not given authority or power to make substantial change. Additionally, librarians of color often find themselves taking on undervalued “diversity work” in collaborations, piling explaining concepts and lived experiences to white colleagues on top of the work itself (Chou & Pho, 2017). There is very little recognition for those who are not in positions of authority or do not formally supervise others, but make substantial contributions to the collaborative work. Likewise, someone may lead within their position, but never manage others. The work is valued as work, but not in terms of leadership.

Methods

We chose a mixed method approach to cross examine the multiple complex factors that are involved in varied experiences with leadership and management over time. For our primary method, we used Constructivist Grounded Theory (CGT), which supports the open-ended collection and analysis of data. Unlike Grounded Theory, we co-constructed theory by taking multiple perspectives and the positioning of researchers and participants into account. We applied an existing theory based on reoccuring themes from the data. CGT does not assume theories are discovered and uses existing theories where they apply (Strauss & Corbin, 1997; Charmaz, 2006). Within CGT, we used a constant comparison to direct our analysis. Constant comparison is a method of Grounded Theory in which data is compared against existing findings throughout the data analysis period.

As we constructed theory from the results, we applied Feminist Theory, which is a method of analysis that examines the relationships between gender and power, and how structures reinforce the oppression of women (Tyson, 2006). We also looked closely at the historical factors that inform current practices. Our feminist critique is informed by intersectionality, as defined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1990), which explores how people with multiple intersecting identities beyond gender, such as race and ethnicity, queerness, and disability, experience overlapping oppressive power structures.

We created a survey to explore the perceptions and lived experiences of library professionals related to leadership and management. This includes librarians with MLIS degrees, paraprofessionals, and students in order to capture the perspectives of newly minted librarians, managers of new librarians, and those interested in mentoring or supporting new librarians. We sent the survey to multiple ALA email listservs (groups for new members of ALA, new members of leadership groups, general leadership, reference, assessment, college and university libraries, diversity and inclusion, technology and scholarly communication) to gather responses. The survey included questions on skills, attributes, and participants’ experiences. We provided a list of skills based on the literature and asked participants to rate their importance. We deliberately designed the survey so that participants would share their own thoughts and values first, without being primed by our list of skills.

We analyzed the data based on the career experience of the respondents. We categorized librarians with 0-6 years of experience as “early career.” Those with 7-15 years we categorized as “mid-career,” and those with 16+ years as “late career.” These determinations are based on the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) criteria for travel scholarships to the biennial conference (one of the few career level distinctions we found from a professional organization). We included pre- and post-MLIS work in determining experience. This differs from the ACRL definition, where they measure based on post-MLIS experience. We wanted to capture all experiences that contribute to how professionals acquire skills during the early stages of their careers. We also asked participants to report degrees earned. Our survey did not involve questions about tenure, but we did note any mention of the influence of tenure.

When we analyzed the data, instead of creating categories before coding responses, we created categories based on prominent themes in the data. Additionally, we used Voyant, an open-source text analysis tool, to track frequently used words, examine phrases, and measure sentiment. With Voyant, we determined the most popular qualities in leaders and managers. We also used it to determine the most common themes from qualitative responses.

Limitations

We sent our survey to ALA-affiliated listservs, which excluded librarians who do not subscribe to those services. We did not ask for a lot of demographic information, including age, race or ethnicity, or type of library in which participants work. According to the literature available at the time we designed the survey, professionals had varying positive, neutral and negative perspectives on how identity affected their paths to leadership. We wanted to give participants an opportunity to address these issues and included a question specifically about whether they encountered challenges related to their identities. As we designed our instrument, we did not design them with feminist critique or intersectionality specifically in mind.

We realized after completion of the survey that “Cis or Trans Woman” and “Cis or Trans Man” may be more accurate labels than the options we provided, such as “Woman or Trans Woman.” We also did not ask for participants’ age or list age as a challenge related to identity. When we presented preliminary data at the ALA Annual Conference in June 2018, we consolidated mid- and late career responses. We realized it was important to separate these responses in the results of this paper, as they are distinctly different career levels.

Results

We recorded 373 responses to the survey. After eliminating responses with less than a 22% completion rate, we had 270 complete responses.

Background and Demographics

The results of the survey included a high percentage of respondents with greater than six years of experience. We wanted a wide range of perspectives, including those who were able to reflect on how their early experiences shaped the rest of their career. This skew prompted us to filter responses (particularly qualitative ones) based on early career (0-6 years), mid-career (7-15 years), and late career (16+ years) to analyze specific perspectives.

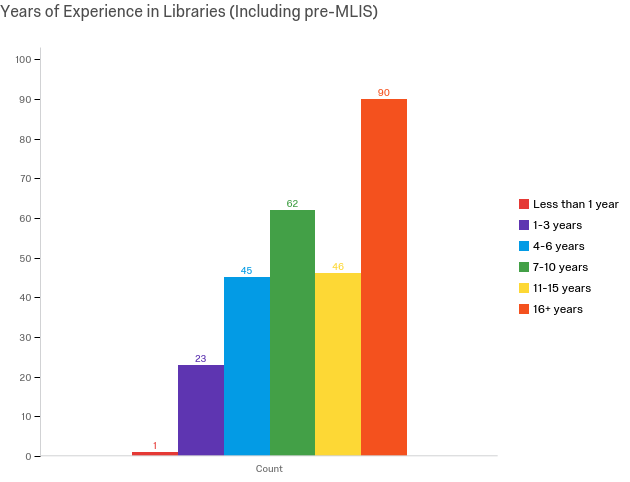

Participants gave information about their years of experience (n = 270). The majority of respondents had 16 years of experience or more (36%). The second largest experience range was 7-10 years (20%). 26% of respondents were early career professionals, with an experience range of 0-6 years. Educational backgrounds among early and mid- to late-career professionals had no difference in proportion, although two early career respondents noted they were currently completing a bachelors or masters degree in library science.

Figure 1. Respondents’ years of experience in libraries, including pre-MLIS experience.

Representation and Challenges Related to Identities

Respondents (n = 270) were 80% cisgender women or trans women and 15% cisgender men or trans men; 1% identified as non binary, 1% preferred not to answer and 0.37% identified as other. Some qualitative responses included mentions of harassment, microaggressions, or bias related to gender:

“One time I was treated particularly unfairly during an internal interviewing situation in which [I] accepted the position but was offered considerably less money that a male counterpart. I had to prepare for negotiation and [speak] out about this inequity. I expressed my concern to my male supervisor / department head and, great as he was, he was not helpful for me because he was particularly conflict averse (although awesome in a lot of other ways).”

“The concerns I’ve faced with regard to these issues haven’t come from fellow employees, but from library patrons, who have occasionally been sexually explicit or harassing towards me and other female employees (non-white employees have faced similar problems, but being white I have not directly faced that problem myself)…”

Identities by Career Stage

While we did not ask for demographic information regarding race, sexual identity, or ability, we did want to gather information about whether respondents faced challenges related to these identities.

| Identity | Early Career [0-6 yrs] (n=42) | Mid Career [7-15 yrs] (n=52) | Late Career [16+ yrs] (n=39 ) | Response Rate (n=182) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 45.23% (n=19) | 76.92% (n=40) | 22.44% (n=11) | 48.35% (n=88) |

| Race or Ethnicity | 14.28% (n=6) | 25.00% (n=13) | 8.16% (n=4) | 18.68% (n=34) |

| Gender Expression | 4.76% (n=2) | 5.76% (n=3) | 0.00% (n=0) | 2.75% (n=5) |

| Sexual Identity | 7.14% (n=3) | 5.76% (n=3) | 0.00% (n=0) | 3.30% (n=6) |

| Accessibility/Disability | 11.90% (n=5) | 3.84% (n=2) | 4.08% (n=2) | 9.89% (n=18) |

| Other experiences intersecting with any of the above or additional issues | 16.66% (n=7) | 19.23% (n=10) | 44.89% (n=22) | 17.03% (n=31) |

The most common challenges participants faced in relation to their identities included gender, race or ethnicity, and accessibility or disability concerns. Respondents often faced challenges related to their ability:

“I have a hearing disability. I often need technical support for meeting in ensuring that I can hear everyone. It doesn’t always work out.”

“I had health issues come up, that included significant exhaustion, brain fog, and executive function issues (along with other symptoms). My boss at the time handled it very badly – he kept pushing me to take on more tasks (in my first year in a new position), did not communicate options to me for leave/additional support (or refer me to the person in the campus structure who managed that for staff), and shamed me for making a necessary specialists appointment. I ended up having my contract not reviewed and was out of work for a year.”

“Mental illness, stigma”

Others faced challenges due to their age, race, or social class:

“When I was younger, people under my leadership would sometimes become angry about a perceived lack of experience in comparison to them…. I believe that I have often had to overcome quite a bit of disrespect as a woman of color in our field. Underneath others’ leadership, I have found less support from managers as I grow older and more experienced. Aging leadership clearly see me as a threat to their positions, and have cut me off from professional opportunities. Administrators sometimes shut down committees when the team selects me as a leader. This has happened to me 4 times in my current organization.”

“[H]onest conversations about race and social class. I was told to tone down my pride about coming from a working class background and being from the south. Learning to hide this identity has helped me connect with academic librarians, who are mostly from upper social classes.”

Some face challenges that are intersectional, including homophobic remarks, crossing personal boundaries (or as the respondent says, “lines I can draw”), and sexist behaviors:

“[My coworker] tells on people and I’m uncomfortable working with her. She is very conservative and the other day she asked me what I thought of gay couples raising children… I would like to work out with someone the lines I can draw. Having an older tentured male professors ask me to make coffee for them for an IRB meeting. They didn’t realize I was a professor (junior), and was there for the meeting. I was shocked and while thinking of a response, they realized their error.”

There were few responses to gender expression and sexual identity challenges that participants faced, but it is important to note identities which may be marginalized within gender issues.

Participants were able to select multiple identities to indicate intersectionality in challenges. It is beyond the scope of this paper to list all of the intersections of identities that exist, but in the data, the most common combinations of intersectional identities included gender and gender expression; gender, race or ethnicity, and sexual expression; gender and accessibility; and gender, race and accessibility.

Comparison of Direct Reports in Highest Supervisory Role

We asked librarians how many direct reports they supervised in their highest supervisory role. More than half of surveyed early career librarians had direct reports. This is higher than expected and highlights the fact that early career librarians are in fact moving into leadership and management roles.

Mid- and late career professionals had greater numbers of direct reports, with 27% having more than 10 subordinates and only 13% having none. Late career librarians supervise more than either other group, which is in line with our expectations. Additionally, 90% of men who completed the survey were supervisors, but only 76% of women were supervisors.

| Career Stage | Gender | 0 Direct Reports | 1-5 Direct Reports | 5-10 Direct Reports | 10+ Direct Reports | Total Responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Career | Men | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Women | 33 | 20 | 7 | 5 | 65 | |

| Non-Binary | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mid Career | Men | 2 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 15 |

| Women | 16 | 38 | 16 | 17 | 87 | |

| Non-Binary | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Late Career | Men | 1 | 4 | 4 | 12 | 21 |

| Women | 1 | 16 | 28 | 20 | 65 | |

| Non-Binary | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

We did not include “Prefer not to answer” and “Other” in these tables due to lack of responses.

Leadership and Management Attributes

In an open-ended question, we asked participants what skills and qualities ideal leaders and managers possessed and to rate their value. These were the most commonly written values, qualities, and attributes:

Leader: vision (170); ability/able (125); communication (83); good (used an adjective describing excellence or competence) (46); communication (33); skills (33); visionary (33)

Manager: ability (67); good (57); skills (56); communication (52); staff (44)

Participants included words such as ability, good, skills, or staff, which were not in our prompted list of valued skills. Skills from the literature that were not valued by our participants (either in the open-ended questions or the value question) included commitment, influence, negotiation, problem solving, dedication, caring, and assertiveness.

Traits valued for leaders across all career stages were vision, ability/able (in this context also meaning competency or execution), good, and communication. Early career librarians valued additional traits such as listening, generating ideas, and thinking about the big picture. Mid- and late career librarians valued other traits such as a focus on people, work, and organization (both organizational knowledge and being organized).

Librarians valued skills, communication, work, and organization in managers across all career stages. Early career librarians valued teams (presumably both teamwork and the existence of teams) in addition to shared ideal traits.

Few people marked any of the qualities “Not at all important” and all except for one category, development, were 0% of the total answers.

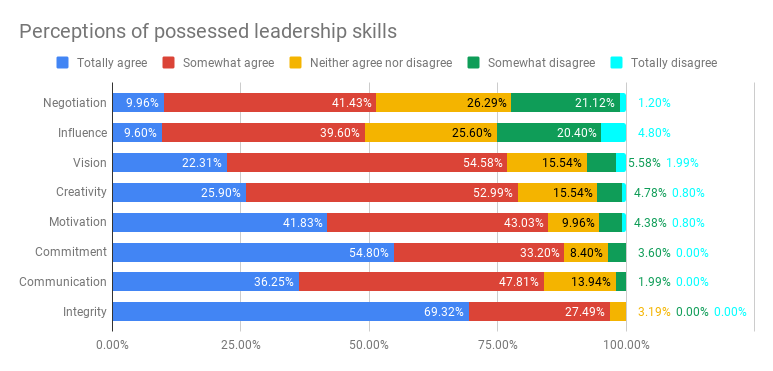

Possessed Skills

We asked participants to rate the extent to which they feel they already possessed leadership and management qualities. Most librarians feel a strong sense of integrity and commitment is needed for leadership, but feel less strongly about their influence or negotiation skills. Overall, librarians feel positively about their leadership skills, with only a handful saying they “totally disagree” about any particular skill. This dedication to integrity is reflected in the responses as well. Librarians who felt their supervisor trusted them or acted ethically were more positive in their responses:

“Experience under a public library director who served with grace and integrity. Taught me how to deal with a board of supervisor who were all men.”

“I reported to an AUL who repeatedly lied to me about important issues. One example: she told me she took a diversity proposal I spent weeks developing to the Dean, who (AUL said) did not support it. I found out from the Dean that she had not brought him the proposal. (This is just one example.) I realized I could not trust her integrity. My reaction was to request to go back to a non-supervisory position. The library lost one of its few minority senior managers (me). I did not have the tools to effectively deal with this situation.”

Figure 4. Respondents’ perceptions of whether they possess specific leadership qualities.

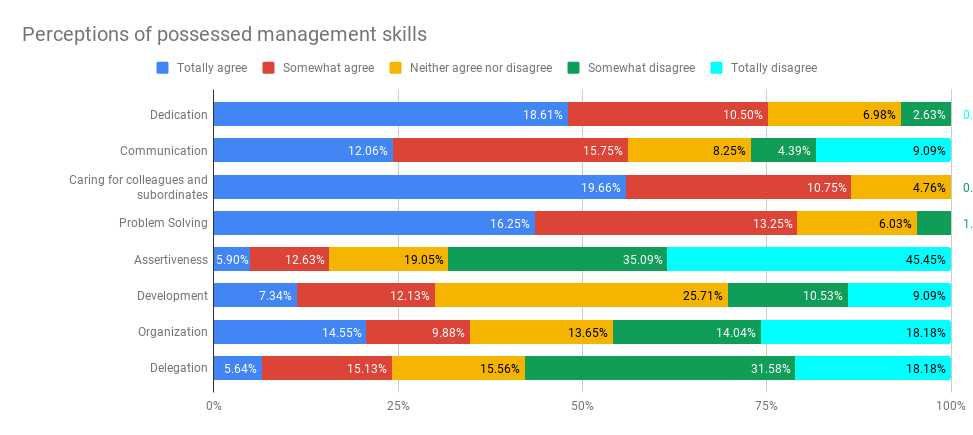

However, librarians are in less agreement over their management skills. Librarians did not rate any of these skills as highly as they did for leadership skills. Librarians feel they have dedication, care for colleagues and subordinates, and problem solving skills. On the other hand, few believed that they possessed assertiveness, development, organization and delegation needed for management. The skills and attributes that librarians rated highly are correlated with caring and empathy, which are represented in the responses as well:

“I had a boss who was very open to hearing from his staff, and I told him that I didn’t like how he treated one of my colleagues; I felt as though he was disrespectful to her, and he listened to me and actually improved his actions towards her from then on. I appreciated that he cared enough to listen and change his actions.”

Figure 5. Respondents’ perceptions of whether they possess specific management qualities.

Generally, responses were positive across career stages. Early career respondents have fewer “totally agree” responses.

Additionally, communication was a choice in both questions, and librarians rated themselves differently. 36% said they totally agree that they have leadership-communication, but only 12% said the same for their management-communication. Communication was a challenge expressed in almost every section of the survey. Participants rated themselves poorly for their communication proficiency and wrote in open-ended questions about experiences they had with others. These two examples show a positive and a negative experience with supervisors:

“I had a manager who made a point to always stand up for her subordinates. If they were wrong, she would take them aside and personally talk to them about how the situation could have been handled better, rather than berating them in front of the public or co-workers. This lead to improved confidence, particularly in tough situations with public service.”

“On the negative side I’ve had supervisors who have failed to communicate information that later became public and caused problems in the library…. Previously, I worked with a leader who actively refused to advocate for the library and it cost us resources (laptops and other tech that I didn’t even know we had access to. I learned about it via gossip with other librarians and staff.)”

We asked participants to share when they have received feedback about these leadership and management skills to see if they actually possess them. A few paraprofessional respondents noted they did not receive feedback about leadership or management attributes because they did not have the same formal review processes as professionals. This is notable because it shows a gap in support between librarians with their MLIS and those in libraries who do not have the degree. Generally, feedback mechanisms were informal and came from supervisors and colleagues.

Another common theme was that respondents felt frustrated about the feedback they receive from supervisors. Unspecific feedback, no feedback at all, or informal feedback that does not reflect the formal review were major points of frustration. Below is an example from a respondent who prefers specific, constructive feedback that reflects the supervisor’s understanding of the value of their work:

“I receive generic “thank you for the good work” emails from my supervisor regularly, though I don’t think she has a good idea of the work I do, or of its value to my team”

One major issue that surfaces in this statement is that the supervisor may not understand their work, and does not give appropriate or helpful feedback because they cannot. This shows how miscommunication may be indicative of deeper issues, but we can only speculate because the respondent did not elaborate.

Support, Challenges and Role Models

Several questions on the survey were dedicated to feedback, support structures, and leaders who made an impression on them. Many reported additional types of resources for support in the “other” field. These included webinars, funding for professional development, informal peer mentoring, defunct mentoring programs, leadership training external to libraries. More people reported access to support for leadership training (28%) than formal mentoring (20%) or peer mentoring (18%). This is reflected in many of the qualitative responses, in which respondents note support for acquiring skills, but lack of support for navigating specific situations.

Institutional Support

| Type | Early Career (n=60) | Mid Career (n=105) | Late Career (n=105) | Total (n=270) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Mentorship | 25.00% (n=15) | 19.04% (n=20) | 18.09% (n=19) | 20.00% (n=54) |

| Leadership Training | 18.33% (n=11) | 32.38% (n=34) | 29.52% (n=31) | 28.14% (n=76) |

| Peer Mentorship | 18.33% (n=11) | 17.14% (n=18) | 20.00% (n=21) | 18.51% (n=50) |

| None | 33.33% (n=20) | 21.90% (n=23) | 15.23% (n=16) | 21.85% (n=59) |

| Other | 5.00% (n=3) | 9.52% (n=10) | 17.14% (n=18) | 11.48% (n=31) |

Participants were able to select multiple options for types of support as well as topics that support covered. If someone indicated two types of support, it was counted in both categories. The following were dual forms of support indicated by early career librarians: formal mentorship and peer mentoring, leadership training and peer mentoring, as well as formal mentoring and leadership training. Other forms of support included funding or opportunities for external professional development (continued education, human resources, conferences, webinars, etc.), informal mentoring, training or mentoring for new or select “rockstar” librarians, and lack of support at the senior leadership level.

Topics of Support

Participants shared multiple areas of institutional support they received (n =147). Across all career stages, respondents received the most support for librarianship (or job function) (65.98%). Late career librarians received the most support for training (early 25.00%; mid 23.07%; late 38.33%). Fundraising was the area with the lowest amount of support across all career stages (3.4%), which aligns with the literature. Write-in topics of support from early career librarians included promotion and tenure, general orientation to the library and institution, teaching, institutional assessment, mentoring and leadership and professional development. Some listed “none,” or no support.

Overall, participants were moderately satisfied with the support they received. There were few extreme responses (either extremely satisfied (11.56%) or dissatisfied (7.54%)), with the majority marked moderately satisfied (33.17%). Yet, we found dissatisfaction in some of the open ended answers. This could be because priorities vary by organization. For example, academic librarians on the tenure track would need more support for publishing than public librarians.

Our questions about support focused on organizational support, but many respondents wrote about interpersonal support they received (or did not receive) from supervisors, mentors, or senior leaders in the organization. Many of these respondents were looking for emotional support to trust their own decisions rather than wanting their supervisor/mentor to make a decision for them. They did not have legitimacy or did not trust their own power to make certain decisions, and needed backup for making hard choices. Support is critical, as shown by one of the responses:

“I have needed support primarily in two areas: negotiating for budget and dealing with difficult personnel issues. In the first case, I needed political support from my administrator: how to build coalitions and be persuasive in order to accomplish my goal. In the second, I needed organizational support from my administrator: how to operate within the personnel system to solve the problem.”

Discussion and Analysis

In terms of our research question, we found that many opportunities and challenges have arisen as libraries evolve. Support for rising leaders requires librarians to recognize their own power to advocate for themselves and to use that power to create a supportive environment for others. Since librarianship is a feminized profession, we used the lens of feminist critique to analyze the results of our study when speaking of power. We focused on historicism in feminist theory, to explore how the history of leadership in librarianship impacts current practices. Furthermore, it is important to analyze the study through a feminist lens informed by intersectionality as we seek to interrogate the profession’s claims to value diversity, inclusion, and equity, despite the lack of changes in the power structure to promote equity. This way, we can take a more accurate look at the progress in addressing calls to action.

White women are now more proportionately represented in leadership, a trend reflected in our data and the literature. Yet there is still contention about who holds power based on how we associate leadership with certain behaviors and identities. Representation is the first step to equity, but more work needs to be done to shift power from those who have historically held it. Our research undercuts existing assumptions that librarianship is more egalitarian because we are less male dominated, that women leaders are inherently feminist leaders, and that more diverse representation will mean inclusive practices.

Additionally, the number of early career librarians in supervisory roles was much higher that we hypothesized. When we designed our study, we were looking at career support as a barrier to preparation for leadership and management, but as we read through the responses, the frequency of experiences pointed to systemic issues. Issues related to race, sexual expression, and other marginalized identities are impacting a lot of early career librarians, but we did not realize to what extent. A great deal of the literature that influenced our original study focused on the individual methods of professional development, disassociated from systems of power that maintain the status quo and keep power in a small number of hands. POC in management positions from Bugg’s 2016 study reported a range of perceptions about identity as helpful, hindering, or neutral to gaining leadership positions and varying levels of ambition. Originally, we thought lack of ambition was an intrinsic motivation, but our analysis revealed that there are external factors as well. The feminist lens helped us look at the larger picture regarding how our organizational structures and individual institutions uphold systematic oppression (e.g., classism, racism, sexism).

We need to examine our relationships to and support of oppressive structures not just in the field at large but within individual libraries. Members of marginalized groups, especially people of color and those who identify as LGBTQIA, experience hidden workloads, microaggressions, early burnout and lower retention. They have less access to and support for opportunities within their work and leadership roles than their counterparts. The profession can change this by implementing institutional policies for conduct and intervention, prioritizing retention, and incorporating anti-oppression practices into support systems and decision-making. Librarianship has documented issues with retention for librarians of color (Bugg, 2016; Chou & Pho, 2017), which directly relates to the lack of people of color represented in leadership positions. Many of the managers from Bugg’s 2016 study received opportunities to gain leadership skills through professional development but felt a lack of support within their libraries. Librarians need to reevaluate and account for the impact of barriers for marginalized in our assessments of how leadership potential is demonstrated, how leaders are retained, and the value of diverse perspectives.

For librarians who aspire to leadership, there can be a disconnect between learning which skills are important, recognizing those skills in yourself, and discovering the methods to obtain those skills. The majority of these “skills” are hard to capture with concrete measurements because they are personal qualities. Skills like organization may be acquired, but qualities such as integrity are characteristics. We did not distinguish these in our survey, and neither did our respondents. We wanted to observe respondents’ perceptions of the concepts, and we anticipated they would use skills and qualities interchangeably. Professionals may enter librarianship with varying individual skills or qualities, and access to learning opportunities or training may vary. We found this can create difficulties for librarians to self-assess, demonstrate abilities, and request feedback, which are major ways for librarians to recognize the skills they need to grow. This hinders progress, as self-advocacy is an important part of demonstrating leadership ability.

Librarians across career stages generally agreed on what they value in leaders and managers. Communication, integrity, and commitment were important qualities to participants. However, it was evident from open-ended responses that these values were not implemented well by some leaders. This aligns with a feminist critique of librarianship that points out how we fall short of what we say and do within organizations, despite aspirational values of transparency, community building, empowering others, and information sharing (Yousefi, 2017). This dissonance can be seen in the responses regarding communication: it is one of the most important identified traits of both leaders and managers, yet many participants rated their own leadership-communication more positively and management-communication more negatively. Many of the traits we desire in leaders have both masculine and feminine coding and may be perceived differently based on the leader’s background (Richmond, 2017). Attaching identities like gender, race, age, and ability to who can and cannot embody or perform leadership traits is a reflection of our relationships to power, however conscious or unconscious.

Figure 7. Beyonce says, “I’m not bossy. I’m the boss.”

Historically, librarianship has perpetuated hierarchical power structures in which leaders were white men. Women—more specifically, white women—were targeted as the ideal professionals to carry out orderly tasks and support researchers through care. The overemphasis of care, moral attachment and service that we currently glorify in librarianship (Ettarh, 2017) continues to perpetuate historical structures in which power is consolidated in few hands (Higgins, 2017; Richmond, 2017). The primary way librarians demonstrate power or influence is through long-term experience or accelerated accomplishments. This reinforces the need for a feminist framework, as mentioned earlier, for shared power in which librarians recognize privilege, cultivate interdependent partnerships rather than serve, and advocate for themselves to address this imbalance of power.

Creating organizations that are supportive, evolving, and inclusive requires that librarians take action to correct these imbalances. In the survey, we noticed an interesting pattern that librarians valued care-related qualities and believed they also possess these qualities. This aligns with the concept of the ethic of care, which prioritizes interpersonal relationships as moral virtue (Higgins, 2017). However, librarians placed less value on qualities related to influence such as assertiveness, negotiation, and delegation, and did not believe they possessed them. This discrepancy and aversion to risk may be influenced by servant leadership. This leadership style implies power is derived from moral standing but requires the leader to relinquish some amount of power in order to “deserve” the position, a starting place not historically afforded to marginalized groups. Higgins (2017) asserts that skills and qualities shown to be effective and valued in leaders should be championed over likability or collegiality, as it unnecessarily disadvantages women in leadership positions. We need to reevaluate whether supporting librarians who exhibit perceived moral care leads to effective leadership.

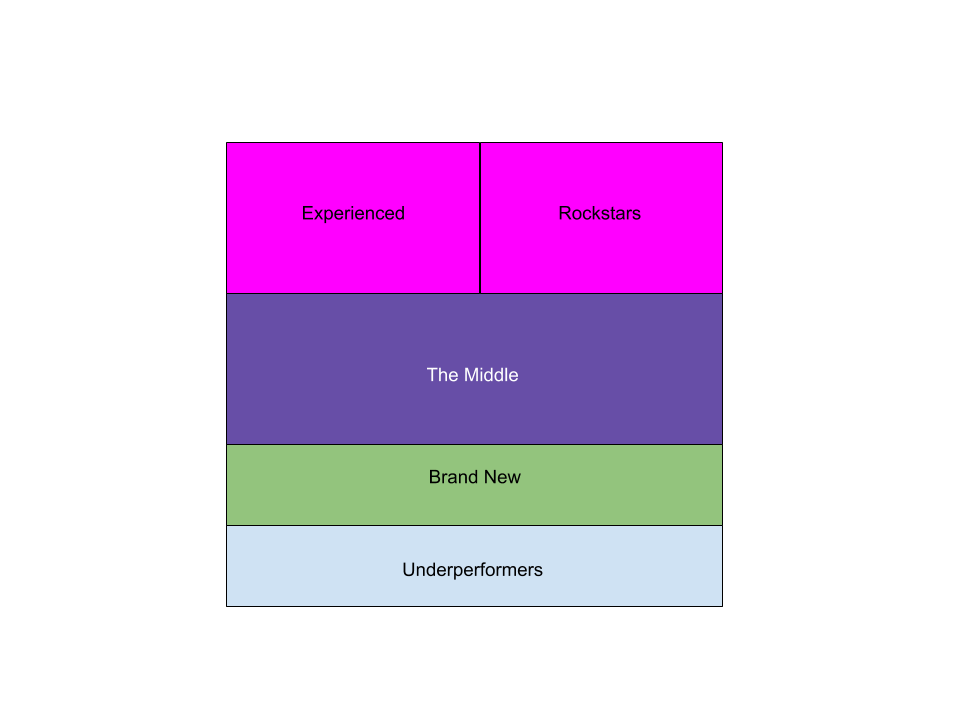

We categorized librarians based on how they did or did not demonstrate influence and leadership skills or qualities. “Experienced” librarians, generally mid- to late career, gained power through relational and organizational influence. “Rockstar” librarians, often early or mid-career, gained a sense of power through ambition, influence through common vision, accomplishments and accelerated responsibility. If positions of servant leadership are deserved based on these paths, those with hidden potential may be at a disadvantage. We labeled librarians with potential but little experience as in “The Middle.” They are still developing experience or ambition, may feel disempowered by leaders, and struggle with imposter syndrome when demonstrating achievements. Librarians in The Middle differ from underperformers or novices in the profession. New competencies (e.g. emerging service areas) and pre-MLIS experiences create opportunities for librarians to be new but not novices. If we are to support librarians of color who may fall in “The Middle,” we must consider cultural competencies and precarious situations that librarians of color navigate as demonstrations of leadership, rather than continue to undervalue the complexities of their experiences.

Respondents of this study revealed examples of lack of support as well as self-disempowerment. Members of marginalized groups can fall in The Middle because they may not have been conditioned to recognize opportunities nor develop leadership skills due to associations of leaders who typify traditional ideals. They may also internalize disempowerment from leaders, colleagues, or external systems of oppression to avoid making themselves highly visible and therefore subject to discrimination through self-advocacy. Some of these challenges surface because of risk aversion, which supports and continues oppressive structures, a false sense of neutrality, and paths of least resistance.

Conclusion

Though new values and additional representation in leadership indicate progress within missions and goals, libraries continue to “replicate libraries of the past instead of looking to the needs of library users and workers of the future” (Askey & Askey, 2017). We still build and recognize leaders based on traditional methods and values.

There are few mechanisms for people rising up in the profession to demonstrate their abilities outside of experience or taking initiative. Most of the focus in library literature has been on who current leaders are and what experience they have shown, not how they get to be leaders. Yet, it is necessary to tailor support to each individual librarian and their challenges. Some practices that support scaffolding (which ultimately lowers barriers to mobility) include clear, constructive, and specific feedback; clearly communicating vision; recognizing individuals’ strengths and weaknesses; helping others recognize their strengths and opportunities; and allowing ongoing, iterative development rather than perpetuating a culture of reactionism and perfectionism. It is especially important to create spaces for open dialogue that includes honest and supportive conversations about identity, given that people with marginalized identities experience the harmful effects disproportionately.

As we move away from traditional work and traditional ideas of leadership, those who currently hold positions must examine their relationship to power by using it to effectively create a legacy for the future. Early career librarians who may take on positions of power now or later must also examine their relationship to power through self-advocacy. It is a cultural shift that requires work from individuals, organizations, and the profession at large. If we are to prepare the next generations of librarians to lead among rapid changes to librarianship, we must intentionally revise relationships to power, scaffold new paths for those with potential to advance, and create inclusive organizational structures going forward.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our editor Amy Koester, and our reviewers Sofia Leung and Ali Versluis for supporting the journey of this complex article. Your insights, observations, and additional readings helped make this article much richer. We also want to thank Ryan Litsey and Denisse Solis for advising us on the framework of our findings.

References

Askey, D. & Askey, J. (2017). One Library, Two Cultures. Feminists among us : Resistance and advocacy in library leadership. S. Lew and B. Yousefi (Eds.). Sacramento: Library Juice Press.

Aslam, M. (2018). Perceptions of Leadership and Skills Development in Academic Libraries. Library Philosophy and Practice. Retrieved November 5, 2018, from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1724/

Birsel, A. (2015). Design the life you love: a step-by-step guide to building a meaningful future. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.

Bugg, K. (2016). The Perceptions of People of Color in Academic Libraries Concerning the Relationship Between Retention and Advancement as Middle Managers. Journal of Library Administration. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01930826.2015.1105076

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory : A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications.

Chou, R. L., & Pho, A. (2017). Intersectionality at the Reference Desk: Lived Experiences of Women of Color Librarians. The feminist reference desk: concepts, critiques, and conversations. M. T. Accardi (Ed.). Sacramento: Library Juice Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan. L. Rev., 43, 1241.

DeLong, K. (2013). Career Advancement and Writing about Women Librarians: A Literature Review. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 8(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8CS4M

Douglas, V. A., & Gadsby, J. (2017). Gendered Labor and Library Instruction Coordinators. Presented at the ACRL 2017 Conference, Baltimore, MD (pp. 266-274).

Ettarh, F. (2017, May 30). Vocational Awe? Retrieved from https://fobaziettarh.wordpress.com/2017/05/30/vocational-awe/

Farrell, B., Alabi, J., Whaley, P., & Jenda, C. (2017). Addressing Psychosocial Factors with Library Mentoring. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 17(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0004

Faulkner, A. (2016). Teaching a New Dog Old Tricks: Supervising Veteran Staff as an Early Career Librarian. Library Leadership and Management. Retrieved from https://journals.tdl.org/llm/index.php/llm/article/view/7206

Fleming, R. & McBride, K. (2017). How We Speak, How We Think, What We Do: Leading Intersectional Feminist Conversations in Libraries. Feminists among us : Resistance and advocacy in library leadership. S. Lew and B. Yousefi (Eds.). Sacramento: Library Juice Press.

Grint, K., Jones, O. S., & Holt, C. (2017). “What is Leadership: Person, Result, Position, Purpose or Process, or All or None of These?” The Routledge Companion to Leadership. Storey, J., Hartley J., Denis, J. L., Hart, P., & Ulrich, D. (Eds.) New York: Routledge.

Harris-Keith, C. S. (2016). What Academic Library Leadership Lacks: Leadership Skills Directors Are Least Likely to Develop, and Which Positions Offer Development Opportunity. Journal of Academic Librarianship. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0099133316300799

Herold, I. (2014). How to Develop Leadership Skills: Selecting the Right Program for You. Library Issues, 35(2), 1–4.

Higgins, S. (2017). Embracing the Feminization of Librarianship. Feminists among us : Resistance and advocacy in library leadership. S. Lew and B. Yousefi (Eds.). Sacramento: Library Juice Press.

Hines, S. (2019). Leadership Development for Academic Librarians: Maintaining the Status Quo?. Canadian Journal of Academic Librarianship 4(February), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.33137/cjal-rcbu.v4.29311.

Irwin, K. M. & deVries, S. (2019). Experiences of Academic Librarians Serving as Interim Library Leaders. College & Research Libraries. 80(2), 238-258.

“Library Leadership Training Resources”, American Library Association, December 9, 2008.

http://www.ala.org/aboutala/offices/hrdr/abouthrdr/hrdrliaisoncomm/otld/leadershiptraining (Accessed November 5, 2018).

“Leadership and Management Competencies”, American Library Association, October 3, 2016.

http://www.ala.org/llama/leadership-and-management-competencies (Accessed November 5, 2018).

Lew, S. (2017). Creating a Path to Feminist Leadership. Feminists among us : Resistance and advocacy in library leadership. S. Lew and B. Yousefi (Eds.). Sacramento: Library Juice Press.

Ly, P. (2015). Young and in Charge: Early-Career Community College Library Leadership. Journal of Library Administration, 55(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2014.985902

Martin, J. (2018). What Do Academic Librarians Value in a Leader? Reflections on Past Positive Library Leaders and a Consideration of Future Library Leaders. College & Research Libraries. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.6.799

Morris, S. (2019) ARL Annual Salary Survey 2017–2018. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries.

Olin, J., & Millet, M. (2015). Gendered Expectations for Leadership in Libraries. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. Retrieved from https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/libleadgender/.

Phillips, A. L. (2014). What Do We Mean By Library Leadership? Leadership in LIS Education. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 55(4), 336-344.

Richmond, L. (2017). A Feminist Critique of Servant Leadership. Feminists among us : Resistance and advocacy in library leadership. S. Lew and B. Yousefi (Eds.). Sacramento: Library Juice Press.

Rooney, M. P. (2010). The Current State of Middle Management Preparation, Training, and Development in Academic Libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 36(5), 383–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2010.06.002

Silva, E., & Galbraith, Q. (2018). Salary Negotiation Patterns between Women and Men in Academic Libraries. College & Research Libraries. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.0.0.%25p

Stewart, C. (2017). What We Talk About When We Talk About Leadership: A Review of Research on Library Leadership in the 21st Century. Library Leadership & Management, 32(1). Retrieved from https://journals.tdl.org/llm/index.php/llm/article/view/7218

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1997). Grounded theory in practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Tyson, L. (2014). Critical theory today: A user-friendly guide. New York: Routledge.

Wilder, S. (2017). Delayed Retirements and the Youth Movement among ARL Library Professionals. Association of Research Libraries. 9.

Young, A. P., Powell, R. R., & Hernon, P. (2003). Attributes for the Next Generation of Library Directors, 8.

Yousefi, B. (2017). On the Disparity Between What We Say and What We Do in Libraries. Feminists among us : Resistance and advocacy in library leadership. S. Lew and B. Yousefi (Eds.). Sacramento: Library Juice Press.

Appendix A: Survey Questions

Demographics

1. Are you a

- Man or Trans Man

- Woman or Trans Woman

- Nonbinary

- Prefer Not to Answer

- Other [text entry]

2. How long have you worked in libraries?

- Less than 1 year

- 1-3 years

- 4-6 years

- 7-10 years

- 11-15 years

- 16+ years

3. Select degree(s) earned. Please list any subjects besides library science in the “Other” field. [tick box]

- High School

- Associate

- Bachelor

- Master

- MLIS (or equivalent)

- Doctoral

- Vocational

- Other________ (text entry)

4. On average, how many people have reported directly to you in your highest supervisory position?

- 0

- 1-5

- 5-10

- 10+

Leadership and Management Attributes

5. What are the qualities of an ideal leader?

Text Entry

6. What are the qualities of an ideal manager?

Text Entry

7. How important are these qualities of leadership? (Likert Scale – rate very important to not important at all)

- Vision

- Creativity

- Commitment

- Motivation

- Communication

- Integrity

- Negotiation

- Influence

8. Rate the extent to which you feel you already have these leadership qualities. (Likert Scale – rate totally agree to don’t agree at all)

- Vision

- Creativity

- Commitment

- Motivation

- Communication

- Integrity

- Negotiation

- Influence

9. How important are these qualities of management? (Likert Scale – rate very important to not important at all)

- Dedication

- Communication

- Caring for colleagues and subordinates

- Problem Solving

- Assertiveness

- Development

- Organization

- Delegation

10. Rate the extent to which you feel you already have these management qualities. (Likert Scale – rate totally agree to don’t agree at all)

- Dedication

- Communication

- Caring for colleagues and subordinates

- Problem Solving

- Assertiveness

- Development

- Organization

- Delegation

Demonstration of Attributes

11. Please provide any feedback you have received from a supervisor, mentor, or peer that you demonstrate these qualities. Include how this feedback was expressed (in a formal review, in a meeting, informally).

Text entry

12. Have you faced challenges regarding the following: (Yes or no checkboxes)

- Gender

- Race or ethnicity

- Gender expression

- Sexual identity

- Accessibility/ Disability concerns

- Other experiences intersecting with any of the above or additional issues

13. Describe a situation you have encountered in which you needed support or preparation. What kind of support or preparation was needed and did you receive it? Answer as a leader/manager or as an employee.

Text entry

14. Describe an experience you’ve had being led that made an impression on you and your work.

Text entry

Mentorship

15. What support does your institution provide? Choose from below or add your own:

- Formal mentorship

- Leadership training

- Peer mentorship

- None

- Other [text entry]

16. Rate how satisfied you feel with this support.

Likert scale – rate Very satisfied to very dissatisfied

17. Does this support focus on any specific area, check all that apply.

- Librarianship

- Publishing

- Research

- Training

- Service

- Fundraising

- Other [text entry]

Appendix B: Additional Data Visualization

Figure 8. Respondents’ perceptions of the importance of specific leadership qualities”.

Figure 9. Respondents’ perceptions of the importance of specific management qualities”.

Figure 10. Chart listing experienced and ambitious librarians at the top, “The Middle” representing librarians who show potential in the center, and brand new and underperforming librarians at the bottom”.

Pingback : INFO 203 and Then Some | Hi-Rise Olancha