Revising Academic Library Governance Handbooks

Original Image by Flickr user Sasquatch 1 (CC BY 2.0), with minimal modification by C. Strunk (10 June 2015).

In Brief

Regardless of our status (tenure track, non-tenure track, staff, and/or union), academic librarians at colleges and universities may use a handbook or similar document as a framework for self-governance. These handbooks typically cover rank descriptions, promotion requirements, and grievance rights, among other topics. Unlike employee handbooks used in the corporate world, these documents may be written and maintained by academic librarians themselves1. In 2010, a group of academic librarians at George Mason University was charged with revising our Librarians’ Handbook. Given the dearth of literature about academic librarians’ handbooks and their revision, we anticipate our library colleagues in similar situations will benefit from our experience and recommendations.

By Jen Stevens, Theresa Calcagno, Claudia C. Holland, and Nathan Putnam

Background and Context

There are three handbooks at George Mason University (Mason) governing individuals in various faculty positions: the Academic/Professional Faculty Handbook, the Librarians’ Handbook, and the Mason Faculty Handbook, which covers instructional faculty.2 Librarians at Mason, a young institution founded in 1957, are classified as professional faculty, a non-tenured faculty classification. As such, librarians are governed by the University’s Administrative/Professional Faculty Handbook (A/P Handbook), as well as by the Librarians’ Handbook (Handbook), which became an appendix of the former in 2000. The Handbook contains provisions that apply only to professional faculty librarians. Although the history of the Handbook is not well documented, its precursor was an evaluation and promotion document that was used by library administration as early as the 1970s.

Librarians who hold a professional faculty position at Mason (~45) are members of the Librarians’ Council (Council), which plays a significant governance role by defining the standards for librarian rank, contract renewal, and promotion in the Librarians’ Handbook. Our Handbook differs significantly from the A/P Handbook because the Librarians’ Handbook includes a statement on academic freedom, a professional review process for contract renewal and promotion, professional ranks, and some aspects of the grievance and appeal processes. Consequently, our Handbook is more analogous to the Mason Faculty Handbook.

In late 2009, the Council voted to review and, as needed, revise the Handbook, especially sections related to professional peer review and librarian ranks. We began in the summer of 2010 with the appointment of an ad hoc handbook review committee that was selected by Council officers and approved by the library’s senior administrators. The A/P Handbook was under review at this same time, so revising the Librarians’ Handbook concurrently made sense. Our colleague representing the library in the A/P Handbook group was also appointed to chair the Council’s ad hoc committee, and her dual role proved to be most advantageous to our revision process.

Literature Review

Although there is a substantial body of literature regarding employee handbooks as a whole (most of it in Business and Human Resources), relatively little has been published on creating and revising faculty handbooks, let alone librarian faculty handbooks. Articles that do include library faculty tend to do so in a cursory fashion. One example is a 1985 Chronicle of Higher Education article “Writing a Faculty Handbook: a 2-Year, Nose-to-the-Grindstone Process” that provides a brief description of the recommended process from a legal standpoint and an outline for how to structure the resulting document. This outline includes librarians, along with other “Special Academic Staff and Categories,” but only as a line item (Writing 1985, 29).

One of the few articles describing the actual process of writing and revising faculty handbooks, James L. Pence’s “Adapting Faculty Personnel Policies” focuses solely on instructional faculty (Pence 1990). A more detailed faculty handbook outline that addresses material applicable to librarians is provided in Drafting and Revising Employment Policies and Handbooks. 2002 Cumulative Supplement (Decker et al. 2002, 456-511), but it is more of a prescriptive example from the standpoint of human resources law rather than a “how to” or case study.

Although it is unclear why library faculty are not more fully included in such articles, one reason may be the lack of conformity regarding librarian status in higher education institutions. As surveys such as Mary K. Bolin’s “A Typology of Librarian Status at Land Grant Universities” indicate, librarian status varies widely (Bolin 2008). For the purpose of her survey, Bolin grouped librarian statuses into “Professorial,” “Other ranks with tenure,” “Other ranks without tenure,” and “Non-faculty (Staff)” (Bolin 2008, 223). These statuses span a continuum, with “Professorial” being closest to instructional faculty who have tenure and research requirements and “Non-Faculty (Staff)” being the furthest. More variation may exist within those statuses; for instance, at some institutions, “Non-Faculty (Staff)” librarians are represented in Faculty Senate, while at others, they are not (Bolin 2008, 224).3

We are not aware of any research that reports how many academic librarians are covered by broader faculty handbooks. Given the wide disparity of librarian status, and the fact that librarians may or may not be part of their institution’s larger faculty handbook, it isn’t surprising that librarian handbooks have not received a lot of attention in the literature.

Process

Our review began in earnest in September 2010. We met weekly, which made it easier to maintain discussion continuity from one meeting to the next, and began with deciding on an approach and a tentative timeline. Our initial deadline was April 2011, which mirrored the working deadline for the A/P Handbook. Because both handbooks had to be approved by Mason’s Board of Visitors, we believed it would be advantageous to submit ours as part of the A/P Handbook.

To learn more about the history of pertinent sections, we talked to our library colleagues who worked on previous versions of the Handbook. We reviewed the Academic College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Standards for Faculty Status for Academic Librarians (2007) as well as librarian governance documents from other colleges and universities in Virginia.4 These document reviews confirmed that our handbook was already aligned with the published ACRL standards, provided insight into how governance was handled at other institutions, and gave us ideas to consider for our own handbook. For instance, we considered aligning the professional peer review process with the annual administrative review process and adjusting the professional review calendar.

We met with representatives from the University’s Human Resources Department, the Provost’s Office, and the Office of University Counsel several times to ask questions and learn more about the legal and administrative issues and policies affecting our Handbook. Information shared during these meetings indicated the roles of different faculty handbooks at Mason and how ours fits into the broader institutional picture.

Each committee member volunteered to revise specific sections based on their interest and experience. We reviewed sections as they were revised, rather than in any specific order. Several sections (e.g., Introduction, Professional Development) were revised quickly, whereas others involved deeper discussion. For example, we thought it was critical to discuss the sections on Librarian ranks and professional review together because they were so closely related. The complexity and sensitivity of this subject matter sparked discussions that spanned multiple meetings and content iterations.

Section discussions were often quite detailed, covering all possible aspects–from the overall intent and purpose of the content to the specific definitions of words and phrases. Decisions about the level of textual vagueness or detail desired had to be made. Proposed revisions were considered, modified, discussed, and modified again. We spent a lot of time on word choice to make the document more cohesive and minimize ambiguity. To enhance the Handbook’s professional appearance, we standardized punctuation, capitalization, and format, and removed references to specific web sites.

Throughout our work, we needed to share working documents easily with one another (there were seven committee members), which we accomplished using Dropbox. This practice alleviated some problems with version control, but edits were occasionally made to multiple versions of the same document that later needed to be reconciled. The “track changes” functionality within Microsoft Word was also critical to share changes we had made and add comments and questions. As the work progressed, the committee Chair compiled the revised sections into a final draft for review and created a list of major revisions to share with Council members and reviewers.

Feedback from our colleagues was critical, and we gathered it using online polls and surveys, and town hall meetings. We frequently presented reports at Council meetings to inform the larger body of our progress, receive verbal feedback, and address any questions or concerns.

Both the University Librarian and Vice President/CIO for Information Technology (CIO), the Libraries’ most senior administrators at that time5, were required to review and approve our revised Handbook prior to submission of the final draft to HR for integration with the A/P Handbook. To expedite this process, we gave the University Librarian revised sections as they were completed for his review and comments, and we met with him on several occasions to discuss his questions and concerns.

The revision schedule changed during the process, largely because it took us longer to revise some sections than we originally anticipated. Other delays occurred after we wisely decided to mirror the A/P Handbook revision schedule, which lagged behind ours. For example, protracted discussions of the grievance and termination sections of the A/P Handbook lead to delayed revision of those same sections in the Librarians’ Handbook. We wanted to ensure that whatever modifications the A/P Handbook Committee made would not conflict with the rights conferred librarians in our existing Handbook (e.g., grieving salary or filing a grievance as a group). We also chose to defer to the A/P Handbook for parts of the grievance and termination sections that were duplicative, which streamlined our document. A more flexible timeline meant our revision process took longer than it might have otherwise, but our revised text did not conflict with the revised A/P Handbook. As a result, it enabled submission of a combined, single document from HR to the Board of Visitors at one time rather than in pieces.

We finished the Handbook revision in July 2011 and sent electronic copies to the CIO and the University Librarian for review and comment. The University Librarian provided his feedback in late November and our final revision was completed in February 2012, after which it was sent to Human Resources for integration into the newly revised A/P Handbook. Subsequently, the combined document was submitted to Mason’s Board of Visitors, who approved it on March 21, 2012.

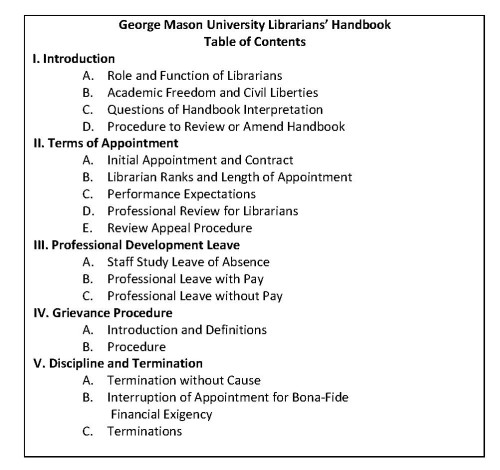

Table 1: Table of Contents. George Mason University Librarians’ Handbook (George Mason University 2012b).

Professional Peer Review for Librarians

Because professional review is the most important aspect of self-governance defined in our Handbook and detailed in our Council’s Bylaws, a brief description of this process is in order.6 The Council’s Professional Review Committee (PRC), a standing committee, consists of seven elected members who serve staggered two-year terms; a librarian is eligible to serve on the committee after having gone through this peer review process at least once. The University Librarian, in consultation with the PRC Chair, designates subcommittees of three reviewers for each reappointment or promotion review. Librarians are permitted to request that a subcommittee member be recused if a potential conflict of interest exists.7

Based on a librarian’s hire date (see the Professional Review Calendar section below), their review begins with submission of an annotated curriculum vitae (CV) or a “dossier” to the PRC. The dossier is, in fact, a notebook containing the librarian’s CV and detailed documentation of all accomplishments (e.g., publications, presentations, awards, grants, offices held, etc.) achieved during a specific period of time. Mason librarians report progress in three areas: 1) professional competence; 2) scholarship and professional service; and, 3) service to the university and the community. However, only information related to scholarship and service are included in the dossier; content related to professional competence, as well as the required supervisor’s evaluation letter, are neither reviewed by nor available to the PRC subcommittee.

Points to Consider

During the revision process, we identified several major issues we believe readers will benefit from learning how we handled, or did not handle. They are grouped by issues related to Handbook content and those related to our revision process (see below).

Professional Review Calendar

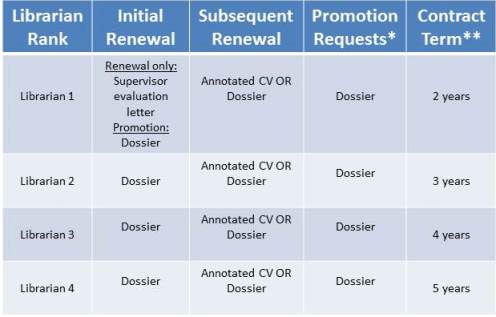

A critical situation the committee wanted to rectify was the inequity in time newly hired librarians were allowed before their initial professional peer review. All librarians, regardless of rank, receive an initial two-year contract.8 Librarians hired before March in a calendar year must submit their CV or dossier for review the first January after they are hired. However, librarians hired later in a year may have up to twice as much time before their initial review (Table 2). Several adjustments to the calendar were considered, but ultimately, we could only incorporate minor changes due to limits imposed by the Provost’s and University Librarian’s schedules, which, in turn, are dictated by the University’s fiscal year.

*For a subsequent promotion, the dossier should cover all professional activities since the last promotion.

** Contract Term = Rank + 1 year

Table 2. Documentation Requirements by Librarian Rank and Review Type (George Mason University 2012b).

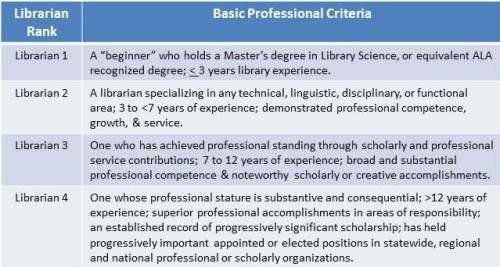

Librarian Ranks

Handbook content related to librarian rank required a lot of attention, with one example being the basic definition of a librarian. The Handbook defines a Mason librarian as a library employee with a professional faculty appointment and an ALA recognized degree9; this definition also confers Council membership. Table 3 details the basic criteria required for each librarian rank.

Table 3. Mason librarian rank criteria (George Mason University 2012b).

Recently, however, professional faculty positions formerly held by librarians have been filled by individuals without an MLS, thus disqualifying those individuals from becoming Council members. Likewise, individuals who hold an MLS or similar degree and are hired in classified staff positions are not eligible for Council membership. The revision committee and Council discussed retiring the library degree requirement, but ultimately did not change the definition primarily because these colleagues would not be subject to professional peer review. If the Council membership definition were changed, three repercussions may take place:

- the Librarians’ Council would no longer be a “Librarians’” Council;

- non-MLS professional faculty would be subject to peer review or there would be two systems of review; and/or

- the Librarians’ Council would be dissolved and all rights conferred by the Librarians’ Handbook terminated.

None of these possible repercussions appealed to Council members at the time.

We also discussed whether to require Librarian 1s to apply for promotion to the Librarian 2 rank as part of their initial reappointment. This idea was dismissed because we were unable to make the desired changes to the professional review calendar. Under the existing calendar, Librarian 1s with no previous experience going up for initial professional peer review might have as little as 18 months of experience in an academic library. This is insufficient experience for advancement to the rank of Librarian 2, which at Mason requires a minimum of three years.

External Reviewers

Composition of the Professional Review (PRC) subcommittee for individuals seeking promotion to Librarian 4 concerned the Handbook committee. Neither the Handbook nor Council Bylaws require reviewers to be at or above the level of the librarian under review or promotion, even though it circumvents potential personnel problems to make this a requirement (e.g., a negative review may be more easily challenged). Because no Mason librarians held the Librarian 4 rank when we revised the Handbook (and there still are none), we wanted to ensure promotion to this rank was conducted by reviewers who could draw from the maximum years of experience possible despite holding the rank of, at least, Librarian 3.

One solution we considered was to invite an external reviewer to participate in a PRC promotion subcommittee. This reviewer would be selected from either the Mason community (non-library), or from another institution. Although external reviewers typically participate in instructional faculty promotion and tenure reviews, we decided this option would not work for us and sought another solution. Eventually, we concluded that all reviewers for a Librarian 4 promotion should be a Librarian 3 at a minimum. Because PRC members are elected on staggered terms, however, there is no way to predict how many Librarian 3s may be serving on the PRC in a given year, nor do we know who has decided to seek promotion until a month before the reviews begin.10

Consequently, to increase the pool of reviewers needed for a given year, we revised the Handbook to allow eligible library faculty not currently on the PRC to be appointed as a reviewer rather than hold an election. This change, which was incorporated into our Council’s Bylaws, ensured that all PRC subcommittee members who review a Librarian 4 promotion bring the experience of at least a Librarian 3 to the process. Furthermore, in years when there are a large number of reviews (15-20) to be conducted, the PRC now has the ability to appoint additional reviewers when needed.

Dossier Requirement for Review

Formerly, librarians being reviewed for each contract renewal and/or promotion submitted dossiers (i.e., often lengthy notebooks) to the PRC that documented their publications, presentations, service, and professional development activities. After much discussion, we proposed that librarians undergoing a second or later reappointment had the option to submit an annotated CV in lieu of a full dossier. Dossiers would continue to be required from Librarian 2s and higher undergoing their first contract renewal and/or all librarians applying for promotion in rank. We thought this option was logical from the standpoint that annual evaluations are required of each librarian, anyway, so an annotated CV would suffice for the purpose of contract renewal. Because an annotated CV is a synopsis of one’s professional activities, it requires less work and documentation than a dossier. The University Librarian approved this option.

Council Approval

Neither the Council’s Bylaws nor the Handbook require members to vote on a Handbook revision. We had to decide whether it was important to seek Council approval of the revised document. After much discussion, we chose to ask for a vote of endorsement before sending a complete draft revision to the University Librarian for his formal review. Council approved the draft by a substantial majority.

Follow Up on Implementation of Revisions

Once our ad hoc committee met its original charge of producing a revised and approved handbook, we were disbanded. We did not develop a plan to implement changes to the Handbook, and neither did the Librarians’ Council. As a result, three years after approval, much work remains to be done. Changes to the Handbook required revision of the Council’s Bylaws and procedural changes in the professional peer review process. The Bylaws were revised, but the Professional Review Committee has been slow to incorporate all the procedural changes and decisions described in the new Handbook into the PRC documents that are used to manage and guide the process. This has resulted in continuing confusion with the professional review process, ironically the primary reason we opened the Handbook for revision.

Recommendations for Revising Your Handbook

When we began this project, it seemed overwhelming. Early on, we discussed our revision strategy and made decisions about how to allocate and accomplish the work. Our plans changed over time, of course, and new approaches were proposed and adopted. Re-examination and adjustment of our workflow throughout the project contributed greatly to our success.

Library consolidation, changes in librarian status, and other factors are affecting even long-established academic libraries, public and private. These changes likely require modifications to documents governing librarians at these institutions. Despite our institution’s relative youth, we offer the following recommendations to other librarians embarking on a handbook or similar governing document revision.

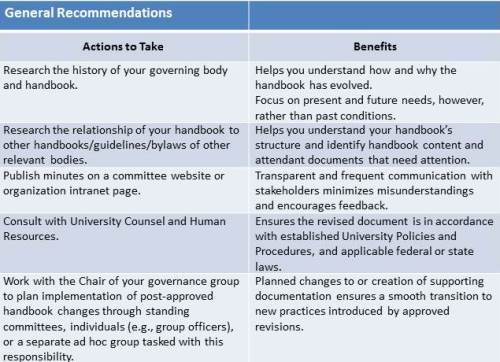

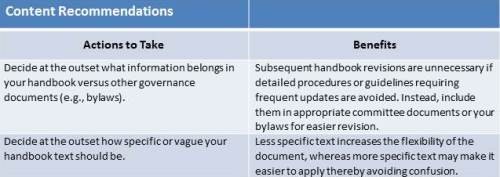

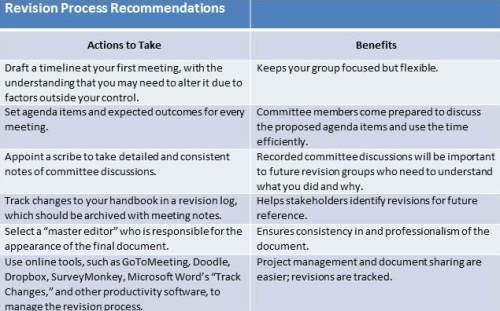

Table 4. Recommended actions and resulting benefits when conducting a handbook revision.

Like most undertakings of this magnitude and importance, the Handbook revision project was extremely time-consuming and, at times, frustrating. Nevertheless, we successfully balanced our Council’s needs within the University’s framework. We were intent on working with our colleagues to create a more professional document that is applicable and fair to today’s members. Most importantly, we gained an intimate familiarity with our handbook—a responsibility all academic librarians with a similar governance structure should work toward. Even when librarians who have a handbook or similar governance documents never have the opportunity or need to revise their handbook, we believe that it is vital to be knowledgeable about its content and ready to advocate for and promote the rights it confers to their colleagues and administrations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our peer review editor, Vicki Sipe, Catalog Librarian at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and our editors at In the Library with the Lead Pipe, Ellie Collier and Annie Pho.

References

Association of College and Research Libraries. Association of College and Research Libraries Standards for Faculty Status for Academic. 2007. Accessed June 5, 2015. http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/standardsfaculty.

Bolin, Mary K. “A Typology of Librarian Status at Land Grant Universities.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2008. v. 34, issue 3, pp. 220-230. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2008.03.005

Decker, Kurt. H. Drafting and Revising Employment Policies and Handbooks, 2nd ed., 2 volumes. New York, NY: Wiley, 1994.

Decker, Kurt. H., Louis R. Lessig, and Kermit M. Burley. Drafting and Revising Employment Policies and Handbooks. 2002 Cumulative Supplement. New York, NY: Panel Publishers, 2002.

George Mason University. Administrative/Professional Faculty Handbook, (2012a). Accessed December 22, 2014. http://hr.gmu.edu/policy/APFacultyHandbook.pdf.

George Mason University. “Librarians’ Handbook,” in Administrative/Professional Faculty Handbook, Appendix C (2012b): 18-32. Accessed December 22, 2014. http://hr.gmu.edu/policy/APFacultyHandbook.pdf.

George Mason University. Faculty Handbook, 2014. Accessed December 22, 2014. http://www.gmu.edu/resources/facstaff/handbook/.

Pence, James. L. “Adapting Faculty Personnel Policies.” New Directions for Higher Education. Fall 1990. 59-68. DOI: 10.1002/he.36919907108

“Writing a Faculty Handbook: a 2-Year, Nose-to-the-Grindstone Process.” Chronicle of Higher Education. October 2, 1985. v. 31, issue 5. p. 28

- Some librarians are governed by documents developed by Human Resources, faculty unions, or content within a Faculty Handbook. There is a dearth of available information regarding handbooks for academic librarians. See Bolin 2008 [↩]

- For the purposes of this article, we define “instructional faculty” as faculty in the more commonly accepted traditional sense (i.e., professors of English or Chemistry) as well as non-teaching research faculty, and term and adjunct faculty, who are also included in this faculty handbook. [↩]

- Professional library faculty at George Mason do not have elected representation in the Faculty Senate. [↩]

- In addition to the George Mason University Faculty Handbook, we read faculty handbooks from the following Virginia colleges and universities: James Madison University, Radford University, University of Mary Washington, University of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University, and Virginia Tech. Since our review, all of these handbooks have been revised except for Radford University and the University of Mary Washington. [↩]

- The University Libraries is now directly under the purview of the Provost. [↩]

- The professional peer review process is distinct from Mason’s professional faculty annual performance review, which takes place between a librarian and his/her supervisor and is required by the A/P Handbook. [↩]

- The standard procedure is that librarians from the same department cannot review one another. This can cause problems for departments with large numbers of librarians. [↩]

- Mason librarians hold multi-year contracts, the duration of which is determined by an individual’s rank. [↩]

- According to the A/P Handbook, “Typical professional faculty positions are librarians, counselors, coaches, physicians, lawyers, engineers and architects…[that] require the incumbent to regularly exercise professional discretion and judgment and to produce work that is intellectual and varied and is not standardized” (George Mason University 2012a, 4). [↩]

- In 2014-2015, the PRC included three Librarian 2s and four Librarian 3s while the entire Council composition was: 2 Librarian 1s, 21 Librarian 2s and 18 Librarian 3s and no Librarian 4s. [↩]