Creating a Student-Centered Alternative to Research Guides: Developing the Infrastructure to Support Novice Learners

In Brief:

Research and course guides typically feature long lists of resources without the contextual or instructional framework to direct novice researchers through the research process. An investigation of guide usage and user interactions at a large university in the southwestern U.S. revealed a need to reexamine the way research guides can be developed and implemented to better meet the needs of these students by focusing on pedagogical support of student research and information literacy skill creation. This article documents the justification behind making the changes as well as the theoretical framework used to develop and organize a system that will place both pedagogically-focused guides as well as student-focused answers to commonly asked questions on a reimagined FAQ/research page. This research offers academic libraries an alternative approach to existing methods of helping students. Rather than focusing on guiding students to a list of out-of-context guides and resources, it reconceptualizes our current system and strives to offer pedagogically-sound direction and alternatives for students who formerly navigated unsuccessfully through the library’s website, either requiring more support, or failing to find the assistance they needed.

Introduction

The way librarians teach research methods and interact with faculty and staff across campus has changed over the years. This is due to a number of factors including reduced or flat budgets, increasing undergraduate enrollment, and changes to content delivery brought on by technological adaptations and users’ needs. Amid these trends, more and more librarians search for active ways to engage novice researchers with instruction that provides guidance and scaffolding into more complex research practices and concepts, instead of instruction that focuses on search mechanics or rote practices. Strangely, since their inception almost 50 years ago, research guides, often used to supplement instruction, have evolved into resource lists despite ample research suggesting this approach has limited efficacy as an instructional approach. Librarians also now often need to look to technology to help support student learning or provide this instruction, with fewer opportunities for in-person instruction or fewer librarians to conduct this instruction.

While academic libraries have long relied on subject guides as a means for supporting students through the research process, the advent of widespread Internet usage allowed libraries to begin making guides available online. This process was streamlined even further with Springshare’s development of the LibGuides platform in 2007. The ease of creating and copying LibGuides has provided librarians a means of developing online, scalable research support for students. In surveying guides across institutions, it is clear that the guides tend to follow a traditional “pathfinder” model that provides students with extensive lists of resources.1 While this is a valid use of guides, the changing expectations of students and faculty as well as more nuanced views of the research process require libraries to rethink the ways they support students as they attain information literacy skills and competencies.

Given these factors, our research focuses on whether or not current practices around the use and presentation of guides, which generally include comprehensive lists of resources without context or instruction, align with information literacy concepts as well as with commonly accepted practices around the way students learn. If the answer is no, what can we – as academic librarians and educators – do to provide a more useful and pedagogically sound option for early career undergraduates? How do we leverage our technology solutions to better serve this constituency who might not receive information literacy instruction through their coursework and might be intimidated by the prospect of asking for assistance from a person at a public service desk?

At the University of Arizona (UArizona), where this research is taking place, 20 liaison librarians are tasked with serving as the primary research support for the entire campus of over 45,000 students, while a smaller group focuses on information literacy instruction to the 4,000-6,000 new undergraduates that arrive on campus every year. The students possess varying levels of experience and skill in research. With the small number of liaisons working with this large community, the need for research support delivery via the library website and other online tools is more and more important. In this article, we will discuss utilizing the LibGuides and LibAnswers platforms to allow students to have more control over their research journey as they navigate the types of resources and library instructional support they need to develop successful research habits and practices. The methods we have used for these changes correspond to research in the application of adult learning theory in library instruction and the conclusions drawn by Kathy Watts in her 2018 analysis of the application of principles of andragogy in online library instruction that “college students… display the characteristics of adult learners. They like to know that their learning is relevant. They learn best when tutorials are problem-based. They come to library instruction with prior learning that needs to be accommodated. They prefer, and are capable of, self-directing their learning.”2

Background

Given the current resource-heavy content in the University of Arizona Libraries’ (UAL) course and subject guides, we began our research by looking for older literature about subject and research guides with the hope of discovering how research guides evolved. While we knew of more recent literature and projects – such as those identified by Alison Hicks in her 2015 article “LibGuides: Pedagogy to Oppress”3 – that position LibGuides as instructional tools, we were surprised to find that researchers have stressed the importance of designing guides with pedagogy at the forefront for decades. Few of the suggestions that researchers previously put forth have been followed, including in the creation of LibGuides at our own institution.

The origin story of library research guides usually starts with topic-specific reference aids developed at MIT in the early 1970s as part of the Model Library Program of Project Intrex.4 These printed aids were called Library Pathfinders and marketed as such. 5 The Pathfinders were expressly “designed to be useful for the initial stages of library research.” They were not intended to be bibliographies, exhaustive guides to the literature, or accessions tools. Pathfinders were a “compact guide to the basic sources of information specific to the user’s immediate needs” and “a step-by-step instructional tool.”6 Canfield (1972) explained that by “a judicious combination of a series of selected informational elements … a Pathfinder enables the user to follow an organized search path.”7 The initial intention was never to create a comprehensive listing of resources but rather a suggested sequence of first steps.

An even earlier precursor may have been the Montieth College Library Experiment at Wayne State University in the early 1960s. Patricia Knapp, an academic librarian and library educator, was an early proponent of integrating librarianship with academic instruction. Knapp’s “path-ways” instruction embedded the library, both its physical collections and the organization of the collections, throughout the four-year Montieth curriculum, building assignments that progressed in complexity as students advanced in their study and understanding of their disciplines.8

Early articles described the strategic purposes of research/resource guides. Alice Sizer Warner (1983) acknowledged that Library Pathfinders could be used as teaching tools and could enhance students’ research skills, though she did not offer specifics on how to accomplish those goals.9 Thompson and Stevens (1985) felt that traditional pathfinders were unsatisfactory because “they provided specific references to information and did not require students to develop their own search strategies.”10 Jackson (1984) described the guides created at the University of Houston-University Park as “search strategy guides.”11 Their guides emphasized a process for searching rather than pointing to specific information resources. The intention was to teach users methods for searching that could be applied in situations where subject guides did not exist. Kapoun (1995) suggested that pathfinders failed to serve their original purpose. He stressed that pathfinders “should not dictate a single ‘correct way’ to perform topical research. Instead they should facilitate individual styles of information gathering…. A pathfinder should offer suggestions, not formulas [emphasis Kapoun].”12

By the late 1990s most libraries had developed online guides to both locally-held and internet-based subject resources, according to research by Cohen & Still (1999).13 While much of the literature continued to focus on the instructional purposes of online guides, many articles described methods, applications, and software that could be used to produce guides. Yet even within these “how-to” articles were references to the instructional uses of guides.

Andrew Cox (1996) described hypermedia library guides. He promoted the incorporation of graphics, images, sound and video files while acknowledging the technical challenges and limitations of existing browsers (Netscape at that time).14 Corinne Laverty (1997) suggested that the Web could function as a library’s desktop publishing system, revitalizing subject guides and pathfinders and allowing the creation and incorporation of interactive library tutorials. In addition to a discussion about technical solutions, she suggested several desired features of online pathfinders, including the “addition of a complete research strategy within a subject area rather than limitation to the traditional list of reference tools,” how to critically evaluate information and write a paper, and links to databases and tutorials.15 The challenge, according to Laverty, was to “take advantage of the versatility and accessibility of the Web in a way that enhances the library learning process.”16

A study of electronic pathfinders from nine Canadian university libraries (Dahl 2001) considered the intended functions of these guides. Dahl felt that pathfinders had an instructional purpose — if they were mere bibliographies, they could not help students learn how to do research.17 Carla Dunsmore (2002) looked at the explicit and implicit purposes, concepts, and principles of online pathfinders. Using both Canadian and American university library pathfinders on three business topics, Dunsmore identified two major functions: “facilitating access and providing a search strategy.”18 Galvin (2005) found that “[p]athfinders which only list resources without providing explanations of the type of information offered in different sources do not teach students to evaluate information.”19 Bradley Brazzeal (2006) compared online forestry research guides to study how the guides incorporated the ACRL’s Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. Findings showed that some guides engaged the users by incorporating features that corresponded directly to elements of a library instruction session. He concluded that research guides had great potential to educate library users by helping them to understand the practical use of library resources and services.20

The time required to create and maintain Internet-based subject guides was noted by Morris and Grimes (1999) in their study of research university libraries in the Southeast. While the creation of guides was time-consuming, the librarians surveyed believed that the guides saved their users’ time in finding quality sites. The additional challenges of creating internet-based guides included the possible need for Web masters, student workers, paraprofessionals, and new software to create, monitor and maintain the guides. Consideration of search strategies or methods of conducting research were eclipsed by the technical challenges of creating online guides.21 In a follow-up study, the same authors concluded that library internet-based subject guides were becoming almost universal.22 The researchers’ use of the term “webliographies,” speaks to their use as a list of links rather than as a pedagogical tool.

Creation of “dynamic subject guides”, at York University, using an open source CMS application was discussed by Dupuis, Ryan, & Steeves (2004). The key objective of their guides was to serve as a starting point for research for undergraduate students. While the guides could be updated and maintained by librarians rather than computing staff, the guides themselves were chiefly search interfaces for library e-resources.23 Moses & Richard (2008) detailed the experience of two university libraries in implementing Web 2.0 technologies (SubjectsPlus and LibGuides) for building online subject guides. At the time of writing in November 2008, the open source SubjectsPlus, developed by Andrew Darby at Ithaca College, had been adopted by 15 libraries.24 LibGuides, a vendor solution developed by Springshare, was reportedly being used by over 400 institutions.

Another early article (Kerico & Hudson 2008) about adopting LibGuides as a web-based platform described the ease of use and functionality of the LibGuides platform. The embedded Web 2.0 features allowed librarians without expertise in computer programming or Web design to quickly create general online resource guides and course-specific subject guides that utilized interactive Web 2.0 features. More importantly, LibGuides could help refine instruction: the platform could make it easy to identify instructional elements that are common to all disciplines and encourage a “refined and collaborative approach to best practices for delivering content online to students and faculty alike.”25

Glassman & Sorensen (2010) suggested several web-based tools for the creation of library subject guides, pathfinders, and toolkits. Options included content management systems such as Drupal, blogging software such as Blogspot and WordPress, and wikis such as MediaWiki. Other options included the open source applications LibData, developed by the University of Minnesota Libraries, and SubjectsPlus. Ultimately Glassman & Sorensen’s library chose LibGuides for their online guides, citing the platform’s ease of use, customizability, strong vendor support, and content sharing.26

A nuanced criticism of research guides was offered by Alison Hicks in 2015. Hicks questioned whether the predominant usage of LibGuides focused far too heavily on the decontextualized listing of tools and resources which isolated research from the reading and writing processes. This was troublesome because it positioned research as static and linear, leading to a predefined or pre-identified truth or right answer. A better solution would be guides designed around research processes, allowing opportunity for students to construct their own meaning-making process. Hicks argued that “when we construct LibGuides around the resources that the librarian thinks the student should know about in order to ace their research paper, we attempt to simplify the processes of research.”27

Ruth L. Baker (2014) suggested that LibGuides could be used more effectively if they were structured as tutorials that guided students through the research process. Such guides would “function to reduce cognitive load and stress on working memory; engage students through metacognition for deeper learning; and provide a scaffolded framework so students can build skills and competencies gradually towards mastery.”28 In one of the few studies conducted to assess the impact of research guides on student learning, Stone et al. (2018) tested two types of guides for different sections of a Dental Hygiene first year seminar course. One guide was structured around resource lists organized by resource types (pathfinder design) while the second was organized around an established information literacy research process approach. The results showed that students found the pedagogical guide more helpful than the resource guide in navigating the information literacy research process. Stone et al. concluded that these pedagogical guides, structured around the research process with tips and guidance explaining the “why” and the “how” of the research process, led to better student learning.29

A study focusing on the influence of guide design on information literacy competency (as delineated in the 2018 ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education) for guides used outside the classroom by Lee & Lowe (2018) showed similar results.30 The pedagogical guide was organized around the research process identified in Carol Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process (1991) and employed numbered steps to lead students through the research process. Students using the pedagogical guide reported a more positive experience, spent more time using the guide, interacted more with the guide, and consulted more resources listed on the guide than students using a more traditional pathfinder (resource lists) guide.31 Even though the study did not reveal a statistically significant difference in the information literacy learning outcomes between the students using the pedagogical guide and the students using the pathfinder guide, the authors proposed that there was a pedagogical advantage to having a more usable guide as well as lessening students’ negative emotions and anxiety related to research.

If, as Hemmig (2005) suggests, the origin of subject guides was Knapp and the Montieth Library Experiment project’s library “path ways”, then one of the central aspects of Knapp’s research has been repeatedly lost and rediscovered, reiterated and ignored, over the last 50 years.32 There has been recurrent consideration of subject guides as pedagogical tools to teach how information is used within the disciplines and how research is conducted, but too often the focus has shifted to the maintenance, readability, format, consistency, language usage, and discoverability of guides. Several authors share the same message of teaching strategies and methods; few reported on the successful implementation of those recommendations.

Our Challenge

As a large, public, land-grant university with over 35,000 undergraduate students, the two small departments of liaison librarians at UAL face a daunting task of supporting students in pedagogically sound ways with limited resources. Librarians often turn to online tutorials and guides to support the large student population. The UAL has a recently updated suite of tutorials that librarians work to embed into early career undergraduate courses. In addition, liaisons consistently collaborate with faculty to develop course guides that support specific classes and assignments. Although this approach has been useful, when we analyzed the usage of our guides as well as the questions that students were asking via chat and the reference desk, we found that the UAL could improve our support for students by investing more effort and energy into developing guides that better connect information literacy practices to the principles of andragogy and that better support students in the meaning making processes of research that Alison Hicks so adroitly champions in her article “LibGuides: Pedagogy to Oppress?” Research has shown that “[l]ibrary instruction seems to make the most difference to student success when it is repeated at different levels in the university curriculum, especially when it is offered in upper-level courses” and that “[a] tiered approach to teaching information literacy is in line with the way many universities teach other literacies, such as writing and math, with introductory skills at the freshman level and then more advanced practice as students matriculate.”33 A Utah State University study that examined the impact of sequenced library instruction reinforces these findings as well as the need to use online learning tools to take advantage of flipped models of instruction when setting up a scaffolded program.34

Given the need for scaling and providing opportunities for scaffolded and flipped instructional experiences that online research guides help fulfill, the use and usefulness of research guides for students is a primary concern for librarians. Courtois, Higgins, and Kapur (2005) studied user satisfaction of online subject research guides at George Washington University and found that while just over 50 percent of respondents rated the online guides positively, a full 40 percent rated the guides negatively.35 Reeb & Gibbons (2004) studied the disconnection between students and librarians’ mental models of information organization within academic disciplines as evident in online subject guides. Their usability testing repeatedly revealed low usage of or dissatisfaction with subject guides. Reeb & Gibbons suggested that an undergraduate student’s mental model was focused on courses or specific coursework rather than the discipline itself. Students found discipline-based subject guides lacking in context – they were confused by subject categorization and frustrated by not finding resources specifically tailored for their informational needs. The authors concluded that creating guides to support specific courses would be more useful to students than discipline-based guides.36 Data on the usage of subject guides produced at UAL bears out previous researchers’ doubts regarding usefulness. The research supports the conclusion that even though librarians may want to rely on subject guides as teaching and research support tools, most guides are underused. In observing the UAL website and existing subject guides in the period from January 1 to May 31, 2019, there is an apparent gap in the way that librarians present information and the way that library users wish to interact with the information being provided. Multiple subject guides produced by UAL have less than 100 views for that five-month period, which amounts to less than one view per day. The most heavily viewed guides on the UAL website focus on a specific, narrow topic or those developed for a specific course or program.

| LibGuide | Page Views |

|---|---|

| AZ Residential Tenants Rules (topic) | 19,287 |

| BCOM 214 (course) | 8,621 |

| GIS & Geospatial Data (topic) | 6,230 |

| ENGL 102/108 (course) | 4,837 |

| Mexican Law (topic) | 4,765 |

| Business (subject) | 2,439 |

| Art (subject) | 1,073 |

| Psychology (subject) | 881 |

| Music (subject) | 682 |

| Nutritional Sciences (subject) | 640 |

Along with issues related to the use of UAL subject guides, an analysis of our current site reveals that novice researchers encounter a number of navigational challenges when looking for guided research and/or instructional support. When looking for guidance, a user must navigate to the “Research and Publish” link, which then activates a dropdown selection where the user can select between links to Research By Subject/Topic, Research By Course/Program (both linking to alphabetical lists of LibGuides), “Learn With Tutorials,” which links to a set of foundational tutorials, “Write & Cite,” which provides links to citation and plagiarism resources and “Support for Researchers,” which links to specialized support for advanced research. While this linear and alphabetical representation of instructional support materials is not uncommon in academic libraries, it creates access challenges and misses an opportunity to demonstrate to students that research is process-oriented and recursive. It also raises the question of whether students understand the terminology in a way that allows them to find the help they need. In addition to navigational challenges, local decisions that were made when LibGuides were first implemented in 2013 further confound the research process. The original templates that the UAL developed for LibGuides pages were designed through a lens that focused heavily on creating a consistent user experience (UX) across guides and are very linear and somewhat rigid in nature. As research on how students learn online has grown, we believe that UX concerns with navigation and consistency must be wedded to design approaches that incorporate the learner experience (LDX). We believe that the purposeful melding of UX and LDX will help ensure that libraries design interfaces that support and enhance “the cognitive and affective processes that learning involves.”37

A Two-Pronged Approach: FAQs and LibGuides

Several attempts have been made by the UAL over the years to address these challenges and better integrate guides into the academic lives of students. One of the more successful projects has involved embedding library resources and instructional materials directly into the campus Learning Management System (LMS).38 This project, named the Library Tools Tab, began in the early 2000s and remains in use today. The goal of the project was to develop a tool that would provide access to a robust, embedded set of library instructional materials and resources through the campus LMS. While the team did succeed in developing and launching a tool that integrated into the LMS, it struggled with maintaining ongoing support and development and was never able to build it into as robust of a learning system as initially intended.

In response to the above observations and experiences, a small working group of librarians began the process of rethinking and revising the UAL’s approach to supporting online student research and learning. At the outset, the focus and intent was to improve the design of our subject and course guides. Our project grew as we worked to incorporate the research and best practices that we had uncovered as part of our research. Several factors influenced this expansion in scope including research conducted by William Hemmig (2005), Jennifer Little (2010), Shannon Staley (2007), Carol Kuhlthau (1991), and Meredith Farkas (2012).

Hemmig’s 2005 article credited Patricia Knapp and the Montieth College Library Experiment project in the early 1960s as the genesis of pathfinders and later subject research guides. Knapp’s work to develop library instruction as part of the college curriculum was user-centered. It was designed to teach students the effective use of the library and its resources, creating both ways for the student to progress from their current state (What they know) to their desired level of knowledge (What they want to know) and methods for the student to navigate the organization of scholarly information resources.39 Knapp explained that “[k]nowing the way means understanding the nature of the total system, knowing where to plug into it, knowing how to make it work.”40 Jennifer Little (2010) pointed to cognitive load theory to inform the creation of pedagogically sound and useful research guides. Little’s suggestions for incorporating cognitive load theory principles into research guide creation included tying guides to specific courses rather than broad subject areas and assisting students in developing self-regulated learning strategies by breaking down research into smaller steps. According to Little, such guides “will motivate students to learn and remember how to navigate and use a wide variety of information resources.”41

Shannon Staley used the results of a 2007 study on the usefulness of subject guides at San José State University to suggest that the prevailing model of subject guides – primarily a presentation of lists of resources – did not match the Information Search Process (ISP) used by students that was first documented by Carol Kuhlthau in 1991.42 Kuhlthau, who focused on students’ information behavior, identified six stages of the ISP: initiation, selection, exploration, formulation, collection, and presentation. Staley proposed that subject guides incorporating “the cognitive process to completing course assignments – steps addressing the different stages of the student ISP – would more closely parallel students’ mental model” and thus prove more useful to and more used by students.43 In 2013, Meredith Farkas and a team of librarians at Portland State University released Library DIY, which is a “system of small, discrete learning-objects designed to give students the quick answers they need to enable them to be successful in their research.”44 The Library DIY approach is grounded in the idea that “Libraries also need to rethink how we create online instructional content, which is often designed based on how we teach. A patron looking for information on how to determine whether an article is scholarly doesn’t want to go through a long tutorial about peer review to find the answer.”45

A common theme across the instruction-focused articles on library guides is the need for libraries to unveil systems and processes so that students can engage in research in a way that supports them as creators, explorers, and interlocutors in the research conversation. After exploring several different ideas, we landed on developing a scaffolded approach that is centered on an online, student-initiated, and self-guided research experience. Our intent is to have a system that addresses discrete research concerns while surfacing the iterative nature of the research process. The centerpiece of the redesign is a set of reconceived Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) pages, developed to support the pedagogical approaches identified by Knapp, Little and Kuhlthau, and heavily modeled on the Library DIY approach – so students have a great deal of personal control in the ways in which they plug into, navigate, and engage with library research.

To begin, we gathered local data by looking at queries submitted to our current FAQ system between Jan.1 and May 31, 2019.The queries represent suggested questions for the FAQ, which theoretically will guide the user to their topic via a keyword system. However, for the six-month time period, 202 questions did not result in users clicking on a FAQ item. We found that though over half (n=125) of the questions submitted by users were related to account, software or facilities issues — e.g. “How do I renew books when I have fines?” Most of the remaining 77 questions submitted by users dealt with traditionally research-related topics. Citation/copyright help was heavily represented, as were questions about peer review and scholarly articles, general searching, finding liaison librarians, and other miscellaneous research topics. Chat transcripts followed a similar theme. The bulk (n=265) of the 479 sampled questions asked for basic research help — generally of the “How do I find an article about X?” variety or known-item searches, followed by general access issues (such as eBook or database access) then by citation and or copyright help questions. Although the UAL has a multi-search box in a central location on the website homepage, the data gathered from local chat transcripts and FAQ meshed with the research literature and confirmed that students need support related to how they navigate, understand, and apply the steps of the research process, not just ease of access to resources.

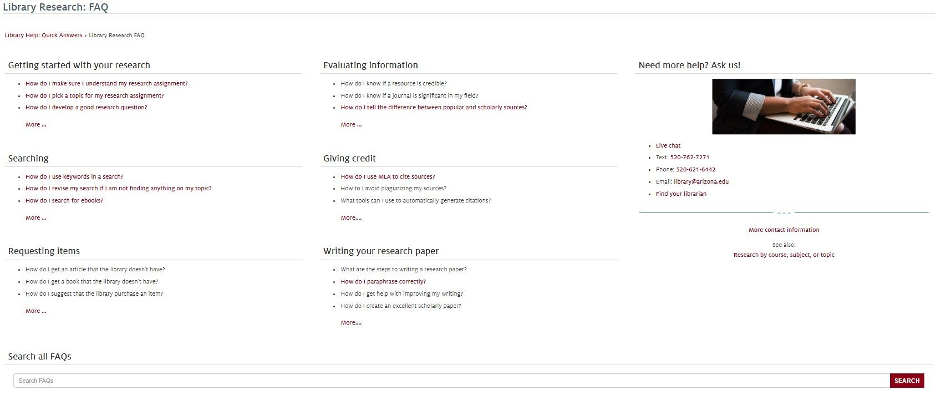

Armed with data and a strong theoretical underpinning, we began the process of creating landing pages that serve as the gateway to the new system. After a few false starts, we worked with our instructional designer to develop the landing page below. It is designed to be visually simple and to help provide a quick on-ramp to research and library navigation as well as straightforward access to help via chat, text, telephone, email, or a liaison librarian. All Answers to FAQs are searchable from the landing page and are organized by category on the sub-pages.

Image 02. Image of Library Research FAQ subpage.

We labeled and ordered the sub-categories to represent the major components of the research process, but also included a search bar so that students can quickly access information that they are seeking.

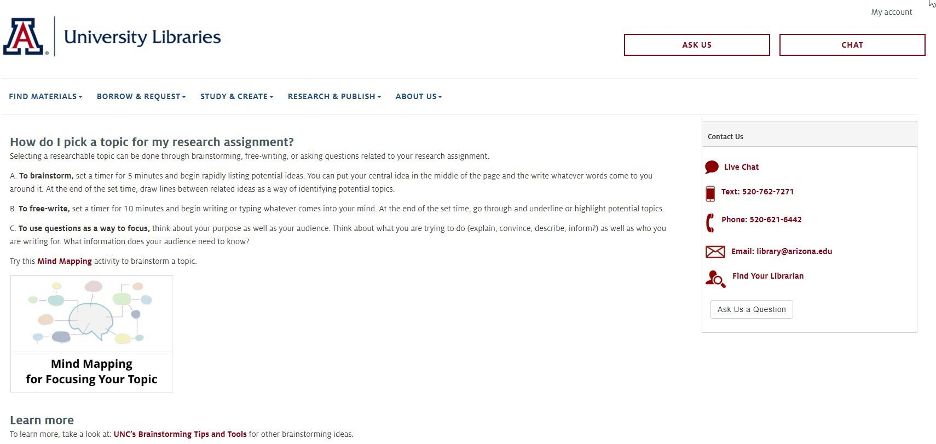

The FAQ answers are grounded in approaching reference through the lenses of pedagogy and andragogy and are designed to scaffold students into increasingly more complex and in-depth information after they have gleaned what they need from the introductory materials. Each FAQ is constructed to answer a specific question as succinctly as possible and then provide links to more in-depth tutorials and resources that students can use as they continue on their research journey. This approach supports Elmborg’s (2002) idea that librarians “must see our job as helping students to answer their own questions”46 and Nancy Fried Foster’s assertion that librarians need to provide opportunities for students “to develop their information seeking skills and their judgement.”47 We feel that this treatment allows us to support students as they take ownership of their searching and learning processes and devise paths through the research process.

Although the initial rationale behind FAQ pages on library websites might have been a means to avoid potential redundancy in the sort of questions asked by patrons to an already understaffed and overtaxed public services staff (West 2015), the authors feel that the platform has potential to provide an additional opportunity for research help, particularly for novice researchers.48 Since FAQs provide an opportunity to create a living document that is updated often (West), the authors hope that the FAQs might also provide an excellent opportunity to create a living pedagogical document that helps support students through the iterative process of research.

Along with restructuring the FAQs, our research helped us identify several ways that we could improve the pedagogical functioning of our course, subject and topic guides. Our original guides were structured to encourage creators to list all resources and content in a single column. This approach was heavily informed by UX best practices and aligned well with those but at times was overly restrictive and pushed creators into developing lists of decontextualized resources.

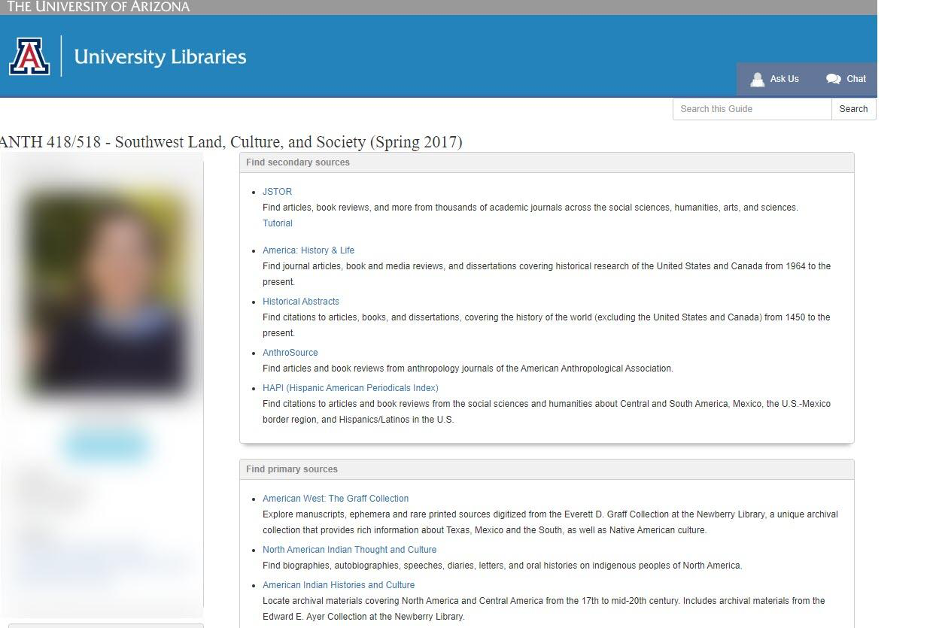

Image 04. Image of

A Linear Course Guide Layout for an Anthropology Course

To address this, we worked closely with our instructional designer to develop guides that allowed the UAL to expand out of our linear, resource centric approach.

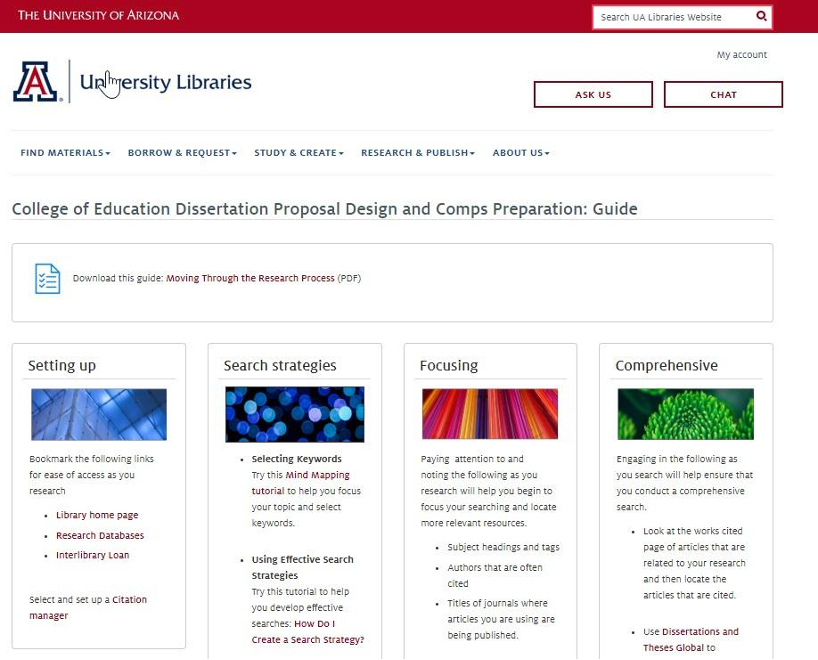

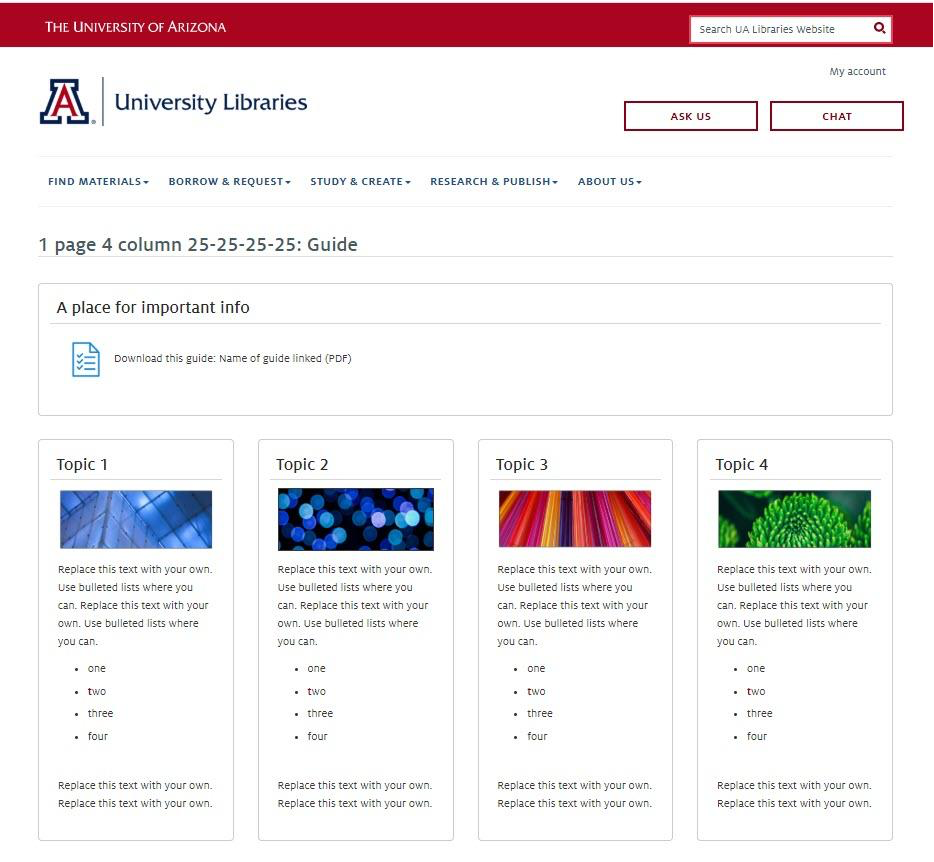

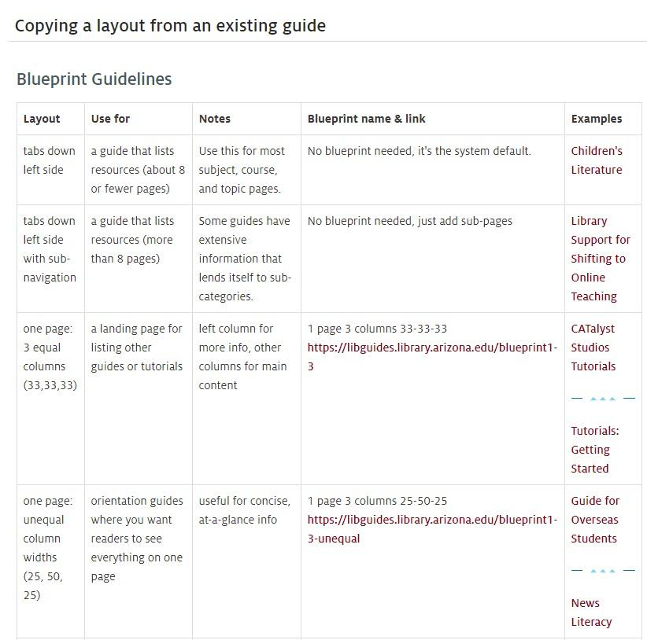

The pilot guides have been well-received by faculty and students, and we soon realized that we would need to implement a system that supported content creators to develop their own instruction-focused guides rather than rely on a single person to develop these guides. To reach the goal of reimagining the way LibGuides can be developed and implemented to better support students in gaining research and information literacy skills, we constructed a system designed to support content creators in developing pedagogically sound guides that adhere to instructional best practices. We want this system to allow for flexibility in presentation and design while maintaining a consistent user experience. We searched across institutions to learn how different libraries managed guides and found that developing blueprint guides would be the most effective way of supporting UAL content creators. The blueprint guides we have developed are meant to synthesize and represent the findings of the many years of research that librarians have conducted on the best ways to teach and learn with library guides. The blueprints are designed to provide creators with flexibility in design as well as efficiency in creation. This support is achieved through providing easy to adapt frameworks as well as specific directions (https://libguides.library.arizona.edu/guidelines/blueprints) on how and why to use a particular type of guide.

Conclusion

Our goal for the new process was to purposefully redesign our existing guides and reference ecosystem to move away from decontextualized lists of resources which encourage students to “engage in a one-stop shopping process.”49 Instead, we would focus on students as active learners constructing their own meaning through the process of research. Doing so would hopefully strengthen students’ sense of self efficacy and ownership of the process, allowing them to become thoughtful contributors to the scholarly conversation. The new system was launched in August 2020, and guide creators are receiving training and support in adapting existing guides as well as in creating new ones. To ensure that librarians across the UAL system are able to successfully implement this new approach, we have developed an infrastructure that starts with pedagogically oriented FAQs that have been designed to adhere to adult learning theory and encourage independent use and discovery. Along with the FAQs, guides have been rethought to better accompany students through the process of research rather than simply provide them with lists of potential resources. Although constructing guides in this way often requires creators to commit to a philosophical move away from a “just in case” provision of resources mindset as well as invest more time in thinking about how to construct paths through a particular research process, we have attempted to lessen the workload by providing a set of easy to duplicate blueprints as well as regularly updated instructions on how to implement these new practices. As of this writing there are six different blueprints with more in development. In the next phase of our research, the authors will be collaborating on a multi-institutional study to assess the pedagogical efficacy of the different blueprints and will share findings in a future publication.

Finally, this model offers a means of bridging the gap between the UAL discovery tool and the more in-depth tutorials and guides that UAL librarians create to support students in their in-class research. It has been designed to provide a way to support students who need help understanding or navigating a specific facet of their research process but are not in need of (or willing to invest the time in) more in-depth instruction. These changes are being undertaken with the intent of developing concrete ways to make the research experience as intuitive and seamless as possible for novice researchers.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to publishing editor Kellee Warren, internal reviewer Dr. Nicole Cooke, and external reviewer Erica DeFrain for their many insightful and generous comments on the manuscript. A special thanks to Nicole Hennig for all her hard work and expertise taking our ideas and turning them into something concrete and functional. Thank you also to Jennifer Church-Duran for being supportive of the need for changes and our research around it.

References

Baker, R.L. (2014). Designing LibGuides as instructional tools for critical thinking and effective online learning. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 8(3-4), 107-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2014.944423

Bowles-Terry, M. (2012). Library Instruction and Academic Success: A Mixed-Methods Assessment of a Library Instruction Program. Evidence Based Library & Information Practice 7(1), 82–95. https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/eblip/index.php/EBLIP/article/view/12373/13256

Brazzeal, B. (2006). Research Guides as library instruction tools. Reference Services Review, 34(3), 358-367. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320610685319

Canfield, M.P. (1972). Library pathfinders. Drexel Library Quarterly, 8, 287-300.

Cohen, L.B. & Still, J.M. (1999). A comparison of research university and two-year college library web sites: content, functionality, and form. College & Research Libraries, 60(3): 275-289. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.60.3.275

Courtois, M., Higgins, M. & Kapur, A. (2005). Was this guide helpful? Users’ perceptions of subject guides. Reference Services Review, 33(2), 188-196. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320510597381

Cox, A. (1996). Hypermedia library guides for academic libraries on the world wide web. Program, 30(1), 39-50.

Dahl, C. (2001). Electronic pathfinders in academic libraries: an analysis of their content and form. College and Research Libraries, 62(3), 227-237. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.62.3.227

Dunsmore, C. (2002). A qualitative study of web-mounted pathfinders created by academic business libraries. Libri 52(3), 137-156. https://doi.org/10.1515/LIBR.2002.137

Dupuis, J., Ryan, P. & Steeves, M. (2004). Creating dynamic subject guides. New Review of Information Networking, 10(2), 271-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614570500082931

Elmborg, J.K. (2002). Teaching at the Desk: Toward a Reference Pedagogy. portal: Libraries and the Academy 2(3), 455-464. doi:10.1353/pla.2002.0050.

Farkas, M.G. (2013, July 2). Library DIY: Unmediated point-of-need support. Information Wants to be Free [blog]. https://meredith.wolfwater.com/wordpress/2013/07/02/library-diy-unmediated-point-of-need-support/

Farkas, M.G. (2012). Technology In Practice. The DIY Patron: Rethinking How We Help Those Who Don’t Ask. American Libraries, 43(11/12), 29.

Foster, N. F & Gibbons, S. (Eds.). (2007). Studying Students: The Undergraduate Research Project at the University of Rochester. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries, 2007.

Galvin, J. (2005). Alternative Strategies for Promoting Information Literacy, The Journal of Academic Librarianship 31(4), 352-357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2005.04.003

Glassman, N.R. & Sorensen, K. (2010) From Pathfinders to Subject Guides: One Library’s Experience with LibGuides, Journal of Electronic Resources in Medical Libraries, 7:4, 281-291, https://doi.org/10.1080/15424065.2010.529767

Grimes, M. & Morris, S.E. (2001). A comparison of academic libraries’ webliographies. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 5(4), 69-77. https://doi.org/10.1300/J136v05n04_11

Hemmig, W. (2005). Online pathfinders. Reference Services Review, 33(1), 66-87. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320510581397

Hicks, A. (2015). LibGuides: Pedagogy to Oppress? Hybrid Pedagogy. http://www.hybridpedagogy.com/journal/libguidespedagogytooppress/

Jackson, R. & Pellack, L.J. (2004). Internet subject guides in academic libraries: an analysis of contents, practices, and opinions. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 43(4), 319-27.

Jackson, W.J. (1984). The user-friendly library guide. College & Research Libraries News, 45(9), 468-71.

Kapoun, J.M. (1995). Re-thinking the library pathfinder. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 2(1), 93-105. https://doi.org/10.1300/J106v02n01_10

Kerico, J. & Hudson, D. (2008). Using LibGuides for outreach to the disciplines. Indiana Libraries, 27(2), 40-42.

Kline, E., Wallace, N., Sult, L., & Hagedon, M. (2017). Embedding the Library in the LMS: Is It a Good Investment for Your Organization’s Information Literacy Program?. Distributed Learning, 255-269.

Kuhlthau, C. (1991). Inside the Search Process: Information Seeking from the User’s Perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 42(5), 361-371.

Laverty, C. (1997). Library instruction on the web: inventing options and opportunities. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 2, 55-66.

Lee, Y.Y. & Lowe, M.S. (2018). Building positive learning experiences through pedagogical research guide design. Journal of Web Librarianship, 12(4), 205-231, https://doi.org/10.1080/19322909.2018.1499453

Little, J.J. (2010). Cognitive load theory and library research guides. Internet Reference Services Quarterly, 15(1), 53-63. https://10.1080/10875300903530199

Lundstrom, K., Martin, P., & Cochran, D. (2016). Making Strategic Decisions: Conducting and Using Research on the Impact of Sequenced Library Instruction. College & Research Libraries, 77(2), 212-226. doi:https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.2.212

McMullin, R. & Hutton, J. (2010). Web subject guides: virtual connections across the university community. Journal of Library Administration, 50(7-8), 789-797, https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2010.488972

Morris, S. E., & Grimes, M. (1999). A great deal of time and effort: an overview of creating and maintaining internet-based subject guides. Library Computing, 18(3), 213-216.

Moses, D. & Richard, J. (2008). Solutions for Subject Guides. Partnership: the Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 3(2), https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v3i2.907

Peters, D. (2012, July 24). UX for Learning: Design Guidelines for the Learner Experience. UX Matters. https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2012/07/ux-for-learning-design-guidelines-for-the-learner-experience.php

Reeb, B. & Gibbons, S. (2004). Students, librarians, and subject guides: improving a poor rate of return. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 4(1), 123-30. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2004.0020

Sizer Warner, A. (1983, March). Pathfinders: a way to boost your information handouts beyond booklists and bibliographies. American Libraries 14, 151.

Staley, S. M. (2007). Academic subject guides: a case study of use at San Jose State University. College & Research Libraries, 68(2), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.68.2.119

Stevens, C.H., Canfield, M.P. & Gardner, J.J. (1973). Library pathfinders: a new possibility for cooperative reference service. College & Research Libraries, 34(1), 40-6.

Stone, S.M., Lowe, M.S., Maxson, B.K. (2018). Does course guide design impact student learning? College & Undergraduate Libraries, 25(3), 280-296. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2018.1482808

Vileno, L. (2007). From paper to electronic, the evolution of pathfinders: a review of the literature. Reference Services Review, 35(3), 434-451. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320710774300

Watts, K. A. (2018) Tools and Principles for Effective Online Library Instruction: Andragogy and Undergraduates, Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 12(1-2), 49-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533290X.2018.1428712

West, J. (2015). Getting Your FAQs Straight. Computers in Libraries 35(3), 28-29.

Wilbert, S. (1981).Library pathfinders come alive. Journal of Education for Librarianship, 21(4), 345-349. https://doi.org/10.2307/40322698

Worrell, D. (1996). The Work of Patricia Knapp (1914-1972). The Katharine Sharp Review, no. 3. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/2142/78247

- Little 2010; Hicks 2015 [↩]

- p. 54 [↩]

- [↩]

- Wilbert 1981; Sizer Warner 1983; Dunsmore 2002; Hemmig 2005; Brazzeal 2006; Vileno 2007 [↩]

- Canfield 1972; Stevens et al 1973 [↩]

- Stevens et al., 1973, p. 41 [↩]

- p. 287 [↩]

- Hemmig 2005; Worrell 1996 [↩]

- [↩]

- p. 224 [↩]

- [↩]

- p. 96 [↩]

- [↩]

- [↩]

- p. 59 [↩]

- p. 66 [↩]

- [↩]

- p. 150 [↩]

- p. 353 [↩]

- [↩]

- [↩]

- Grimes and Morris 2000 [↩]

- [↩]

- [↩]

- p. 41 [↩]

- [↩]

- Hicks [↩]

- p. 111 [↩]

- [↩]

- [↩]

- [↩]

- [↩]

- Bowles-Terry 2012 [↩]

- Lundstrom et al 2016 [↩]

- [↩]

- [↩]

- Peters 2012 [↩]

- Kline 2017 [↩]

- Knapp 82-84 [↩]

- p. 82 [↩]

- p. 60 [↩]

- [↩]

- p. 132 [↩]

- Farkas 2013 [↩]

- Farkas 2012 [↩]

- p. 459 [↩]

- p. 78 [↩]

- [↩]

- Hicks, 2015 [↩]

Tried something along these lines 10 years or so ago. Described here: : https://hdl.handle.net/1920/5972

Idea was well received but it proved a bridge too far for many of our public services staff when it came time to keep the portals “current” and looking “lived in”

I think this is great and am hoping to implement something similar on my campus.

I noticed that you are using Sidecar learning for your website tutorials instead of a guide on the side, which was created by U of A. is there a reason for this? I was just curious. Is it worth the extra cost?