Charles A. Cutter and Edward Tufte: Coming to a Library Near You, via BIBFRAME

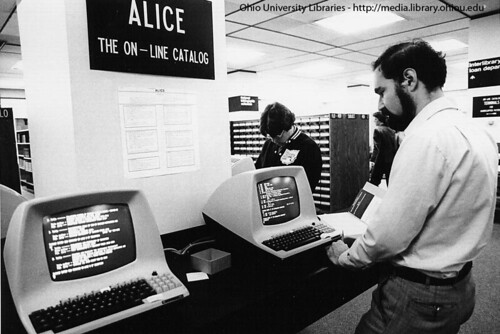

Photo by Flickr user Ohio University Libraries (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In Brief

The library catalog as it exists today is a century-old tool that presents an array of challenges for its users. The manner in which users search for information has not changed since the inception of the paper catalog and its different indices. The electronic records that comprise library catalogs are in a format that is largely the product of cataloging standards and practices designed to replicate printed catalog cards. Additionally, the syntax and terminology of the controlled vocabularies in the catalog are generally alien to its users. We live in an age of Google, and our catalogs should reflect the information-seeking behavior of today’s user, not the user of one hundred years ago.

Cutter and the Modern Catalog

The format of the catalog we have today was largely set forth in Charles A. Cutter’s Rules for a Dictionary Catalog, originally published in 1875. In that work, Cutter suggested that the catalog should “enable a person to find a book of which either the author, the title, or the subject is known.”1 These suggestions mirror the typical indices found in the majority of catalogs today – author, title, or subject while also including an index of classification numbers (another suggestion of Cutter’s). Cutter fully expressed these ideas in his work with Ezra Abbott at Harvard College to create the first known card catalog.2 Indeed, one interacts with these indices in a similar manner to interacting with the separate card catalogs for author, title, subject, and shelflist.

Beyond the methods of indexing and searching, the very format of library metadata in the catalog is dictated by the “analog” catalog. The determinant for structuring MARC was its direct predecessor – the catalog card itself. In her book Henriette Avram, creator of the MARC metadata schema, acknowledges that the catalog card shaped the format of MARC as the Library of Congress continued producing cards for distribution, as well as retrospectively converting existing bibliographic data in library catalogs into MARC format. If one looks at a catalog card and a record in an electronic catalog, they are remarkably similar. Beyond the metadata schema itself, the rules for description of items perpetuate the formatting of data to make entries fit all on one card through standardized abbreviations seen in AACR2.3

The knowledge and tools needed to successfully navigate the catalog can be difficult to learn and so are rarely used by the majority of library patrons. For example, the searching help information at the University of Arkansas extends over seven different pages. Searching by subject headings can be frustrating and confusing, even for librarians. Perhaps a patron is looking for a book about early maps of the arctic regions, and so chooses to search the subject index in the catalog. The patron tries different permutations of headings “Maps — Arctic regions” or “Early maps — Arctic regions” and after a few more attempts, gives up in frustration. The “correct” heading for this is, confusingly, “Arctic regions — Maps — Works to 1800.” Not only are the terms themselves esoteric, the syntax of subject headings is a syntax unknown to many.

Despite its limitations, the library catalog has served the information seeking behaviors of its users well for the past century. If a user knows how to manipulate and structure search entries, the electronic catalog in its present form is an excellent discovery tool. Indeed, the catalog as it exists today is a reflection of a century of adjustment and manipulation by librarians and patrons. The concepts of controlled vocabulary, shelflist browsing, and convenience of searching an index are key contributions to access made by catalogers and the catalogs they create. Beyond these concepts, the curated and authoritative metadata generated by catalogers is also of significant value in the keyword search centered information seeking behaviors of internet and library users.

However, many information seekers prefer a Google search to a search in the library catalog. Based on colloquial evidence, most librarians can affirm that Google, not the library catalog, is the “first line” for information discovery. Furthermore, in a recent post on the Chronicle of Higher Education’s website, Brian Mathews further attests to user frustration with the current structure of library catalogs and their inherent difficulties in navigation and use. Google provides a single search interface for a wide variety of resources. With one search, a user can discover images, webpages, Google Scholar, Google Books and a wide variety of other online resources. Search strategies can be very informal and still return reasonably applicable results. Many libraries are attempting to address this preference through the implementation of discovery engines, such as Summon and Encore, that offer a single search interface for the information resources accessible through the library. Google is now the default resource for information seeking – so much so that it is not uncommon for librarians to encounter individuals who assume that libraries will be obsolete because of Google’s dominance.4

It is perhaps now a trope to refer to libraries in the age of Google. However, this does not obviate the evidence that libraries do indeed exist in an age of Google, and that by and large, individuals seeking information see Google as their primary resource, their first line of inquiry. Naturally this unnerves many librarians who see libraries and the collections they maintain as an authoritative, and perhaps definitive, repository of knowledge that can answer a broad swath of inquiries. What, then, can librarians do to address this preference for Google as a device for information discovery?

BIBFRAME

Not since the advent of the catalog as we know it today have librarians been able to fundamentally rethink the nature of the catalog and how it is used to serve the information seeking behaviors of its users. This ability comes from the ongoing development of the metadata schema referred to as BIBFRAME, which is powered by linked open data. BIBFRAME will help to free library metadata from the silos in which it has been kept for fifty years, and will also allow this data to be interoperable with a far wider web of data, in addition to allowing for a re-thinking of the design and arrangement of the catalog. Furthermore, the change in rules for metadata creation, represented by RDA, will also help library metadata to be more useful, though perhaps to a lesser extent than BIBFRAME. RDA is designed as a rule set for entering metadata into many different schema – MARC, Dublin Core, and BIBFRAME. However, without the changes that BIBFRAME represents, RDA is largely a cosmetic change to library metadata.

BIBFRAME and Linked Open Data

In May 2011, the Library of Congress announced an initiative to examine the possibilities of moving library metadata in legacy formats (chiefly MARC) into a wider web of data and knowledge available on and supported by the internet. In a report dated November 21, 2012, the Library noted that MARC has been an incredible success story in facilitating the machine automation of many library functions. However, the authors of the aforementioned report on BIBFRAME point out that MARC is perhaps outdated, and it is the responsibility of librarians to ensure that library metadata is fully integrated with existing metadata and web standards. In response to this need, the Library of Congress has put forward BIBFRAME (short for Bibliographic Framework) as a recommended replacement for MARC as a metadata schema. BIBFRAME, working in the arena of linked open data, will move library metadata into a much broader network of information. Indeed, the report highlights this change:

As libraries become part of this larger web of data, by leveraging the use of stable identifiers to reference clearly differentiated entities, focus will shift from capturing and recording descriptive details about library resources to identifying and establishing more relationships between and among resources. This includes related resources found on the web, and especially those beyond the traditional bounds of the library universe. These relationships – these links – drive the web, transforming the information space from many independent silos to a network graph that branches out in every direction. Relationships help search engines and other services to improve search relevancy and, most importantly, help users find the information they are looking for.

This quote implies, but does not specifically state, BIBFRAME’s use of linked open data for building web links and metadata into a larger “semantic web”. Proposed by Tim Berners-Lee in 2001, linked open data is the supporting framework for a larger movement called the semantic web. The semantic web, supported by linked open data, aims to describe the relationships between linked items on the internet. The vast majority of the internet is structured with links that do not describe the nature of the links between pages or objects – a typical hyperlink. In their article on the state of the semantic web, Bizer, Heath, and Berners-Lee highlight this by stating “In the conventional hypertext Web, the nature of the relationship between two linked documents is implicit, as HTML is not sufficiently expressive to enable individual entities described in a particular document to be connected by typed links to related entries.”5 The semantic web aims to make information use and discovery a richer and more immersive experience through the description of these links – their semantics. Supporters of the semantic web, and linked open data, see a changed information landscape with the implementation and adoption of the semantic web. Computers and networks would be aware of the nature of the links between objects – that an author created a book, as opposed to a simple link between two resources. As Bizer et al describes, “Whilst HTML provides a means to structure and link documents on the Web, RDF (resource description framework) provides a … model with which to structure and link data that describes things in the world.”6 Machines could then suggest related items or ideas based on what a user is seeking, and chooses to display. This concept has the potential of creating a far more contextual experience for users engaging in information seeking and discovery.

Two examples of the possible benefits of placing library metadata in the linked open data arena appear in an essay in Future Internet, as well as in an interview with Thea Lindquist, Associate Professor and History Librarian at the University of Colorado Boulder. The usefulness of this web of linked open data is further described in terms of possible impact for library catalog users:

Jane: How do you describe to people what semantic computing might do for them?

Thea: Usually I say that it associates related concepts, increases findability, context and interoperability, enables semantically rich services (like faceted searching, content recommendations, and visualizations) and allows re-use, re-mixing and re-presenting of data. If they look puzzled, I start by comparing the current web of documents to the web of data. When you search for a term on the web of documents, the computer looks for the string of characters you entered, and it has no idea what the meaning associated with those characters are. When it finds matches, it returns the documents in which they are found, and it is up to you to slog through those and figure out if any of the matches are indeed relevant. If you look for “buck”, you could get documents about a male, antlered animal, a dollar, throwing (a rider) by bucking, giving someone a ride on your bike (this usage may be limited to Minnesota)…you get the picture. On the web of data, supported by ontological structures and intelligent applications, the computer can understand the word “buck” might have different meanings and what those might be, and it will ask you “are you interested in the monetary unit?” (among other things). If you say yes, it will direct you to the relevant data residing within documents rather than the entire document, whether the character string says “buck”, “dollar” or “single”.

As a further illustration, the BIBFRAME document itself describes the possibilities for libraries and users thusly:

As libraries become part of this larger web of data, by leveraging the use of stable identifiers to reference clearly differentiated entities, focus will shift from capturing and recording descriptive details about library resources to identifying and establishing more relationships between and among resources. This includes related resources found on the web, and especially those beyond the traditional bounds of the library universe. These relationships – these links – drive the web, transforming the information space from many independent silos to a network graph that branches out in every direction. Relationships help search engines and other services to improve search relevancy and, most importantly, help users find the information they are looking for.

As BIBFRAME structures library metadata in a way that is easily manipulated by machines, this new schema will free that metadata from the silos in which it has been stored for decades. The nature of library metadata structures has prevented the vast amounts of metadata created by catalogers and librarians over the past forty years from being easily used by tools outside of the library sphere. BIBFRAME is built on XML (eXtensible Markup Language) and RDF (Resource Description Framework), both “native” schemas for the internet. The web-friendly nature of these schemas allows for the widest possible indexing and exposure for the resources held in libraries. Metadata could be indexed by major search engines, and incorporated into conglomerations and indices of linked open data, such as Europeana. As a stopgap measure, Blacklight implementation in the local catalog is useful for exposing library metadata to search engines, but this exposure is done after the fact, and is not integrated into the schema (MARC) itself, creating additional ongoing work for catalogers. BIBFRAME has the potential to “build-in” the ability for library metadata to be indexed easily by major search engines. This ease of indexing and “freeing” of library metadata has the potential to bring users back to the catalog, and back to library websites, as authoritative starting and ending points in information seeking. The addition of the great mass of authoritative library metadata potentially will not only enhance users’ searches through search engines, but those results will also drive users back to the source of that authoritative data – library catalogs. Indicative of the “freeing” power of linked open data, John Overholt’s essay titled Five Theses on the Future of Special Collections highlights the need for library metadata to become part of the linked open data web in his referencing Europeana, to date one of the largest implementations of linked open data in a more user-friendly format. Furthermore, moving library metadata to a schema that is web-native also gives an added benefit to the user that this metadata is easily manipulated by widely available tools and programs for conducting research in the metadata itself. In a blog post on Religion in American History, Lincoln Mullen highlights the potential for research in the metadata, as well as the challenges attendant to conducting that research with metadata structured in MARC. Beyond this “freeing” of library metadata from the catalog for indices and users, the use of web-friendly schemas has other positive impacts for the user and libraries.

During a presentation and a question and answer session hosted by OCLC, Roberta Shaffer of the Library of Congress shared additional information about BIBFRAME. BIBFRAME is currently in an early testing phase. However, if librarians and other interested parties wish to participate in the early phases of this new schema, there are several options to explore at the BIBFRAME website. Perhaps the simplest way to get involved with the new schema is to sign up for the ListServ via email. Also on this website, one can see library metadata structured in BIBFRAME, as well as being able to convert MARC structured metadata into BIBFRAME through online tools. However, as Roberta Shaffer indicated, much of this work is in the early stages and is experimental. To this end, OCLC released a report in June of 2013 that explores the use of BIBFRAME in OCLC’s WorldCat database.

BIBFRAME and the Web

Because of its use of XML, BIBFRAME also has the advantage of being vastly more web-friendly than MARC, and so catalogs could be structured far more differently than they are now, and far more attentive to the needs of catalog users. Librarians have a professional and ethical obligation to their users, as the code of ethics of the American Library Association states: “We provide the highest level of service to all library users through appropriate and usefully organized resources.”

Lorcan Dempsey, Vice-President and Chief Strategist of the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC), recently posted an essay exploring the potential of the library catalog to not only be a tool for local discovery, but also for discovery of items beyond the library’s collections. The breadth of items in Dempsey’s example provides the user with a far broader array of information resources – a process that has the potential to be automated with the adaptation of library data and catalogs to linked open data. However, additional resources do not directly correlate to a better user experience for catalog users. Librarians must look not only to the resources described in the catalog, but also to the user experience.

On Tufte and Catalogs

Perhaps a useful starting point for librarians and designers to think about the design of catalogs powered by BIBFRAME is the work of Edward Tufte. Tufte is perhaps the best theoretician in modern user-centered graphic design. His four books on the display of quantitative information provide some useful guidelines for designers of these BIBFRAME powered catalogs of the future. Tufte is most closely identified with his work in visual displays of quantitative information, but his general ideas and theses can be applied to catalog design, which is the display of information. Indeed, Tufte says, “The design of statistical graphics is a universal matter – like mathematics – and is not tied to the unique features of a particular language.” However, most pertinent to the designer of the catalog is this quote from Edward Tufte:

What is to be sought in designs for the display of information is the clear portrayal of complexity. Not the complication of the simple; rather the task of the designer is to give visual access to the subtle and the difficult – that is, the revelation of the complex.7

A catalog displays a vast array of complex relationships in a way that users can understand. At this time, the navigation of these complex relationships is difficult for many users. Having a single search interface is an acceptable beginning to a better catalog, but this is not the only solution to the problem, nor is it the exclusive solution. A user searching these relationships must search authoritative metadata – the metadata structured by both BIBFRAME and linked open data and generated by catalogers. Users will continue using library resources only if they find them authoritative, and easy to use and understand, not the equivalent of a link farm.

Searching authoritative metadata in a single search box is a start, but remember Tufte exhorts designers to reveal the complex – to “give visual access to the subtle and the difficult.” This process, as described, is facilitated by BIBFRAME, but few users have the ability and inclination to read raw XML code. In Tufte’s essay on the cognitive style of PowerPoint, he highlights that not only words, but also graphics, provide a powerful method of describing complex ideas to users and viewers. This concept could be applied to library catalogs by not presenting metadata in a “list” or “record” format, but instead in a dynamically generated relationships graph. This graph could contextualise the metadata, so that if a user desired to know more about the creator of a given work, then the user could navigate through the graph’s rich information context. This places information resources in a rich context of information in a visual format. It is this contextualization and description of relationships that will make user experience in the catalog richer, but these also are the intended design of BIBFRAME, as stated in the BIBFRAME document:

As libraries become part of this larger web of data, by leveraging the use of stable identifiers to reference clearly differentiated entities, focus will shift from capturing and recording descriptive details about library resources to identifying and establishing more relationships between and among resources. This includes related resources found on the web, and especially those beyond the traditional bounds of the library universe. These relationships – these links – drive the web, transforming the information space from many independent silos to a network graph that branches out in every direction. Relationships help search engines and other services to improve search relevancy and, most importantly, help users find the information they are looking for.

Though the format of the catalog is obsolete, the intellectual endeavor and practice that catalogs represent is undeniably significant and important – not only to the collective memory of society, or the users of libraries, but also to the users of the internet. The formatting of metadata in these catalogs, as guided by cataloging standards, is the result of two hundred years of research, interaction, and revision by librarians. However, this incredible array of metadata is locked away in an outdated metadata schema, with this metadata duplicated and hidden in many discrete library catalogs. Though MARC was a technical innovation in its day, new metadata schema are needed to best serve the needs of our users, as well as the wider public. Librarians are uniquely poised to continue the creation of authoritative metadata that users can trust and use, while adapting that metadata to emerging technologies. Indeed, librarians are already working on the production of new schema – namely, BIBFRAME. This new standard will free library metadata from the silos in which it has been stored for far too long, as well as bringing library metadata into the wider web of linked open data. Beyond this freeing of metadata, BIBFRAME also has the potential to allow librarians and designers to fundamentally re-think the nature and experience of searching the library catalog. In the course of this new iteration of the catalog, it is librarian’s professional responsibility to take time to listen to their users, examine best practices (like those postulated in the work of Edward Tufte), and bring their own information expertise to the versions and implementations of a new generation of catalogers.

Perhaps closing with this reminder from Charles Ammi Cutter is as fitting now in thinking both about metadata standards and catalog design as it was when he first wrote it over one hundred years ago, describing the work of the cataloger in the card catalog:

The convenience of the public is always to be set before the ease of the cataloger.8

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his deep gratitude for the invaluable help of Penny Baker, Collections Management Librarian at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute (and an early user of both BIBFRAME and RDA) for her thoughtful comments and encouragement. The author also thanks his reviewers at Lead Pipe, Hugh Rundle, and Emily Ford. Also, the author’s gratitude goes to Erin Dorney for beginning the process of publication. He would also like to thank his colleagues at the University of Arkansas Libraries, specifically Cheryl Conway, Mikey King, and Elizabeth McKee for their support and guidance in writing and publication. Finally, his thanks go to Jen Dean, who always provides a patient sounding board and peerless editor.

References and Further Reading

Avram, Henriette D. MARC, Its History and Implications. Washington: Library of Congress, 1975.

Avram, Henriette D., John F. Knapp, and Lucia J. Rather. The MARC II Format; A Communications Format for Bibliographic Data. Supplement. Washington: Library of Congress, 1968.

Avram, Henriette D. The MARC Pilot Project: Final Report on a Project Sponsored by the Council on Library Resources, Inc. Washington: Library of Congress; [for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off.], 1969.

Bertin, Jacques. Semiology of Graphics. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983.

Bibliographic Framework as a Web of Data: Linked Data Model and Supporting Services, (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 2012), accessed September 20, 2013, http://www.loc.gov/bibframe/pdf/marcld-report-11-21-2012.pdf

Bringhurst, Robert. The Elements of Typographic Style. Seattle, WA: Hartley & Marks, 2012.

Cutter, W. P. Charles Ammi Cutter. Chicago: American Library Association, 1931.

Cutter, Charles A., W. P. Cutter, Worthington Chauncey Ford, Philip Lee Phillips, and Oscar George Theodore Sonneck. Rules for a Dictionary Catalog. Washington [D.C.]: G.P.O., 1904.

Lima, Manuel. Visual Complexity: Mapping Patterns of Information. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

Manguel, Alberto. The Library at Night. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

Schmidt, Aaron. Walking Paper, accessed November 18, 2013, http://www.walkingpaper.org/

Tufte, Edward R. Beautiful Evidence. Cheshire, Conn: Graphics Press, 2006.

Tufte, Edward R. Envisioning Information. Cheshire, Conn: Graphics Press, 1990.

Tufte, Edward R. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire, Conn: Graphics Press, 2001.

Tufte, Edward R. Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative. Cheshire, Conn: Graphics Press, 1997.

- Charles A. Cutter, W.P. Cutter, Worthington Chauncey Ford, Philip Lee Phillips, and Oscar George Theodore Sonneck. 1904. Rules for a Dictionary Catalog. Washington [D.C.]: G.P.O., p. 12 [↩]

- Charles A. Cutter, “The New Catalogue of Harvard College Library,” The North American Review 108 (1869): 96-129. [↩]

- Henriette D. Avram, 1975. MARC, its History and Implications. Washington: Library of Congress, p. 3. [↩]

- Indeed, an examination of recent search statistics in the University of Arkansas’ Libraries catalog shows that the closest replication to a Google search – keyword searching – is far more popular. Keyword searching represents approximately 31% of patron searches, while subject searching represents approximately three percent. [↩]

- Christian Bizer, Tom Heath and Tim Berners-Lee. “Linked Data – The Story So Far,” International Journal on Semantic Web and Information Systems (IJSWIS) 5 (2009): 3, accessed (September 20, 2013), doi:10.4018/jswis.2009081901 [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Edward Tufte, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. (Cheshire, Conn. : Graphics Press.), 191. [↩]

- Cutter, p. 5 [↩]

A clarification: BIBFRAME is not wedded to XML; that is just one possible serialization (and at this point JSON seems to be favored).

And a question: what role does Blacklight play in disseminating library metadata to search engines? The latest releases of Evergreen, Koha, and VuFind all publish schema.org structured data for their bibliographic metadata and holdings details, so they would be valid examples, but as far as I’m aware Blacklight is not doing anything like this yet.

Hi Dan,

Thanks very much for your comment. You are quite right on the XML and BIBFRAME relationship, I was simply trying to highlight the web-friendly nature of BIBFRAME and used XML as my single example.

Also, my statement on Blacklight is based on the specific implementation of that product at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum Library and Archives. That institution uses Millennium for their ILS (MARC records). Their EAD finding aids are built in Archivists Toolkit. Digital items (PBCore) come from Hydra asset manager, so they do not use Evergreen, Koha, or VuFind. Beyond that, I cannot really comment on their setup, but I think their systems librarian has presented on their implementation if you have questions about their implementation, etc.

Again, thanks for your comments!

Jason

Hi,

Jason’s summary is correct. Blacklight does MARC “out of the box” but I had to extended it to include EAD and PBCore. However, anything that can go into a Solr index can be searched and displayed by Blacklight, so there’s no restriction on the kinds of metadata you can use. It also does not have Schema.org integration yet, but that’s being proposed for the 5.0 release in early 2014.

Adam Wead

Systems and Digital Collections Librarian

Library + Archives, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Adam: Thanks! I was focusing less on the incoming metadata format for Blacklight, and more on the statement that “Blacklight […] is useful for exposing library metadata to search engines” — which it seems currently would mean either as relatively unstructured HTML, or via elements that point to alternate metadata formats.

schema.org integration, on the other hand, is what the major search engines really seem to want; that’s why I mentioned Evergreen, Koha, and VuFind as examples of catalogues that already expose metadata via schema.org. I’d love to help with adding schema.org to Blacklight, assuming the display model relies on some normalization at the Solr level for searching and displaying fields such as title, author, etc

Sorry: reference & instruction guy here:

With such a broad mounting of information in the “open” does that leave libraries prey to market forces or open to wild manipulations (like wikipedia hoaxes) but with metadata)? It seems like part of the silo is a way to maintain the reliability, although you said existing authorities would stay intact.

As far as catalogs being obsolete, I disagree, a lot of people use them and hone them. As you say ” the navigation of these complex relationships is difficult for many users” but I fell like that’s because life is complex as people move between media (physical v. digital), and a catalog reflects that complexity rather than oversimplifying it or giving the illusion of ease. That’s also my job security, so you’re welcome to call humbug though!

http://www.asofterworld.com/index.php?id=1042

Hi Joe,

No need to apologize – I am glad we have a reference and instruction person chiming in! To my mind the sharing of authoritative metadata will not only highlight local collections, but will also serve to improve data in general. However, the creation of that metadata should (and will, I hope) still be done by catalogers. Metadata cannot exist without metadata creators, so there are always going to be those of us that have to feed the metadata machine. I also think the reliability (and interoperability) of the metadata schema will be to some extent guaranteed by the national libraries and organizations behind BIBFRAME.

I think the catalog itself – the idea of the catalog – is still entirely valid and key to libraries and their function. However, the current iteration of the catalog and its metadata is so antiquated – based on and around a format that is well over a century old. Being able to create new and innovative iterations of the catalog is much of my interest in BIBFRAME, and I think much of its potential lies in its power to move library metadata out of silos and into a far more interoperable and user-centered model – a next-generation catalog, if you will.

Hope that clarifies things some – thanks for your comments!

Jason

It does, and thanks for your comments and essay. It reminded me that I need to keep my head up for these things as I provide R&I, because it’ll be a nice shift in the long run.

Pingback : Live Streaming Κάλυψη Συνεδρείων

While Google is known for its “single search box,” that isn’t what brings people back — people use Google because they find the RESULTS useful. Google’s ranking makes use of millions of human decisions to create links between resources, providing a judgment on the relative value of different resources. Library cataloging treats each item as an island (other than some cryptic notes which only display in a full record display), and avoids any semblance of evaluation. Library cataloging completely misses the dynamic of the conversation between resource creators and users.

In this sense, BIBFRAME is no different from AACR+MARC, because it’s the content of the BIBFRAME description that makes a difference, not its format. Right now, BIBFRAME is focused on translating MARC(AACR) to BIBFRAME, which means that nothing innovative is happening at all. Even moving on to RDA will not bring change, as it is based heavily on current cataloging concepts. We have to move beyond descriptive cataloging and start making connections between resources and helping users find the most valuable materials. It’s very similar to Tufte’s approach to data: we have data, but it doesn’t communicate to others until we find a way to make it meaningful to them. “Making meaning” is the big challenge ahead of us.

Pingback : BibFrame: The future of the library catalog | Information Technology SILS 2014